The bodies fruit sorter: Our immune system

Our immune system allows us to thrive despite being surrounded by life-threatening invaders like bacteria, viruses, and cancer. It functions by recognizing invading threats, and removing them – like a tomato sorter removing bad fruits (Video 1). Just like cameras take pictures of tomatoes to direct the sorting machine, immune cells constantly surveil our body to detect threats. By learning from previous infections, our bodies develop an immune memory, similar to how training data allows the sorting algorithm to identify bad tomatoes. Once a known threat is identified by our immune system, whether it be virus, bacteria, or cancer cells, it is systematically removed, just as paddles in a sorting machine remove unripe, damaged, or otherwise unwanted tomatoes.

Although first exposures to a pathogen may make us sick, our immune system can snuff out repeat offenders before they harm us a second time. What if this first infection causes serious harm or death? What if we could safely expose our immune systems to a weakened invader so that our bodies can learn of the threat without needing to experience it fully? Vaccination allows us to do just this, and is similar to the process of training tomato sorters.

Video 1. Tomato sorter.

Vaccines: How we train our immune system to sort good from bad

Imagine a tomato sorter starting with completely random criteria, varying from batch to batch. To sort each batch, a different random criteria is used. These random criteria will sometimes kick good tomatoes out while letting bad tomatoes through, resulting in significant waste. After identifying the rare criteria that resulted in a batch of entirely good tomatoes, we could work back and re-use that same criteria in the future. Accurate sorting would follow only after significant waste. This is akin to how our immune system normally learns. If instead we identified the specific criteria of good and bad tomatoes prior to sorting, we could avoid the training period – which, indeed, is done in reality. Vaccines function similarly: exposure of our immune system to a known threat, modified to minimize disease-causing ability, trains it to remove similar entities in the future without a potentially dangerous learning period involving exposure to the live, dangerous threat.

How our immune cells learn from antigens

Our immune cells detect ‘antigens’ present on invaders to signal for a greater immune response. Antigens may be any molecule present on the surface of invading threats that distinguishes them from healthy cells. In order to achieve vaccination, we present our body with antigens from the target we wish to vaccinate against. Various strategies exist for presenting antigens safely to our body in the form of vaccines1: Inactivated vaccines; live-attenuated vaccines; messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines; subunit, recombinant, polysaccharide, and conjugate vaccines; toxoid vaccines; viral vector vaccines.

The most common vaccines are made from inactivated or attenuated samples. Inactivation entails chemical, heat, or radiation treatment to destroy a dangerous threat. Attenuation, instead, involves weakening of a pathogen to the point that it is significantly less likely to take hold and cause infection. Importantly, these methods leave antigens intact.

With COVID-19, we saw the first adoption of “mRNA vaccine” technology for medical use, although it had been researched for decades in advance. Messenger RNA (mRNA) is the intermediate set of instructions cells follow to produce a protein. DNA is copied into a more transient molecule, mRNA, which then guides protein assembly. By giving cells the mRNA instructions to build a specific threat-associated antigen, our own cells produce the fantigen and expose it on their surface to our immune cells.

Once our immune system learns that a specific antigen marks a threat, regardless of what type of vaccine was used, or if our body first saw the dangerous threat through infection, when it comes across the same antigen in the future it will rapidly remove the connected threat.

How good DNA mutations allow for immune system flexibility

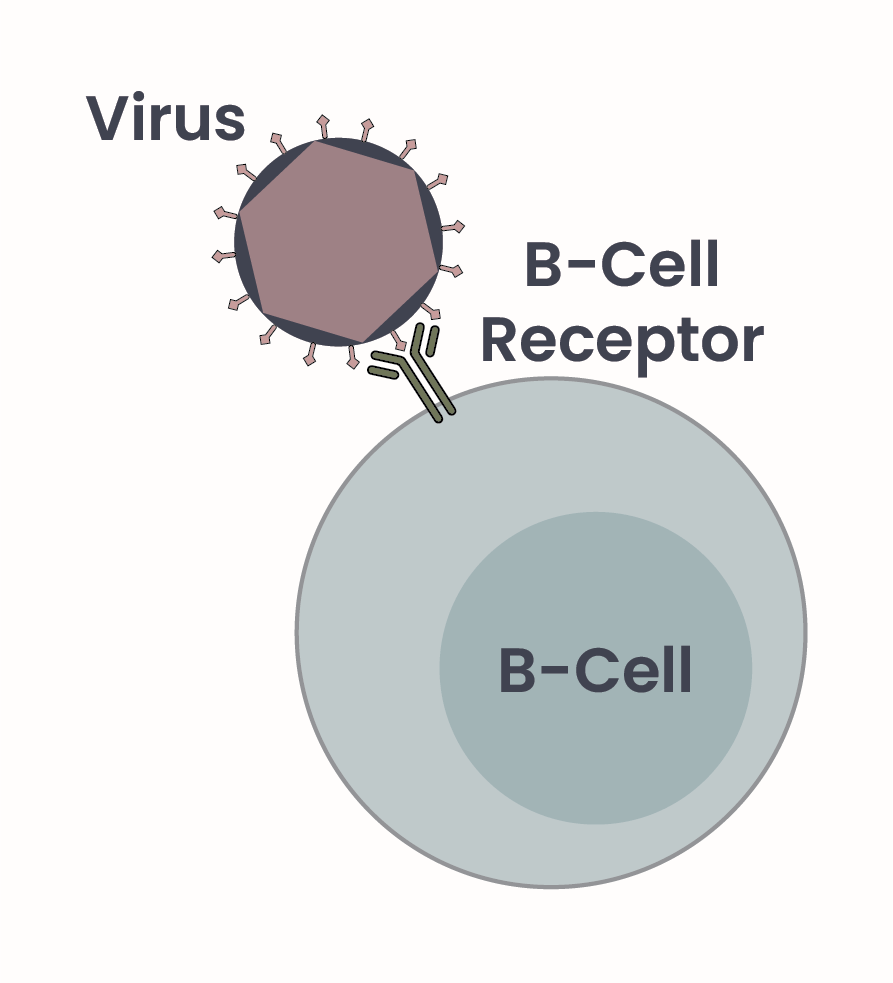

Figure 1. B-cells produce antibodies, Y-shaped proteins that mediate interaction with antigens on biological threats, such as bacteria, cancer, or viruses, as depicted here. Antibodies are also called B-cell receptors when displayed on cell surfaces.

If vaccines are the input we give to tomato sorting machines to train them, then antigens are the characteristics that identify bad tomatoes, and antibodies are the resulting computer code that governs the choices the sorter makes. Antibodies are proteins that directly interact with antigens to signal for the presence of a threat, and direct its targeting by the immune system.

B-cells, a specialized type of immune cell, are responsible for production of antibodies, and initial detection of antigens. When displayed on the surface of a B-cell, antibodies are also called B-cell receptors as they act as a receptor for antigens2 (Figure 1). Each B-cell can recognize only one unique antigen – so how does our immune system recognize all the possible threats? The gene, or set of instructions, that each B-cell uses to make their specific antibody varies greatly from cell to cell thanks to random mutation and thus modification of the antibody-coding gene. While DNA mutations are almost always prevented – mutations are generally not desirable as they could result in cell dysfunction and cancer – they are permitted in this context. Permissive mutation of the antibody gene allows for numerous different B-cells all producing different antibodies, ready to detect anything presented to them.

How an immune system memory is formed

As antibody gene mutation is random, most cells’ antibodies won’t bind anything. Luckily, all you need is one. An antigen and a B-cell receptor ‘meeting’ activates the B-cell. Activation of B-cells causes them to multiply, resulting in a larger cell population that all produce the same antibody. After activation, B-cells can “store” immune memories3 – like identifying a specific characteristic of bad tomatoes – by sitting dormant throughout our body, ready to act. B-cells can also change cell type and become plasma cells. Plasma cells produce the same antibody, but release it into our blood rather than exposing it on its surface – thus it is no longer referred to as a B-cell receptor, but only as an antibody. This circulating antibody will attach to the target invader and facilitate the respective immune response. Circulating antibodies can neutralize the target invader simply by binding to its antigen, or lead to removal of the invader through various immune cells – the paddles of the tomato sorter.

The reason that initial immune responses are weak to a new antigen is that, upon first exposure, there are likely very few B cells that produce the corresponding antibody. Having a large amount of B-cells and plasma cells all expressing the same B-cell receptors and antibodies against a known dangerous threat poises our immune systems to rapidly respond to and clear future instances of the same or similar threats.

Vaccinations safely jump start immunity by exposing our body to inactive antigens of a new threat. The repertoire of diseases we can vaccinate against is ever expanding as our understanding of the immune system expands, and as technology available to us increases. We can already prevent certain types of cancer by vaccinating against cancer-causing viruses such as human papillomavirus (HPV) and hepatitis B. With recent advancements, improving cancer treatment with vaccines is now a growing reality, and vaccinations against specific cancers may even be on the horizon.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Vaccine Types. Updated 2022. Washington (DC): HHS.gov. Retrieved June 9, 2025, from https://www.hhs.gov/immunization/basics/types/index.html. ↩︎

- Pilzecker B, Jacobs H. Mutating for Good: DNA Damage Responses During Somatic Hypermutation. Frontiers in Immunology. Volume 10, Article 438 (2019). doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00438. ↩︎

- Abbas AK, Lichtman AH, Pillai S. Molecular Biology of the cell, fourth edition. B cells and antibodies. Updated 2002. New York: Garland Science. Retrieved June 9, 2025, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26884/. ↩︎

© 2025 WithinOncology. All rights reserved.

This article, including all text, tables, and figures, is the intellectual property of WithinOncology and its contributors. Unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or use of any content without explicit written permission is strictly prohibited. For inquiries, please contact us via the contact form.

Leave a reply to jjones Cancel reply