Cancer screenings are powerful tools of secondary prevention of cancer that can save lives1. How? These tests are used to find disease in people before symptoms show up. Cancers found through screening are generally smaller and less likely to have spread, which significantly improves the chances of successful treatment.

You can think of cancer screening like routine maintenance of your car. When the maintenance light turns on you should still take your car in for regular check-ups – oil changes, tire pressure check, brake inspections – even when everything seems fine, because early detection of a problem can prevent major issues down the line. The same logic applies to our health.

Which cancer screenings are available and who should get them?

While our cars have dashboard indicators telling us when it’s time to go to the mechanic, our bodies don’t come with such preventive alerts. Luckily, health institutions around the World provide cancer screening guidelines that can help us stay on top of our health. In several European countries, healthcare systems send personalized screening reminders—essentially acting like dashboard indicators—and in the United States (U.S.), efforts are underway to implement similar reminder systems for patients1.

Currently, screening for three specific cancers is recommended by health institutions in the U.S. and Europe for average-risk adults (people who do not have a higher risk due to family history or other specific factors): breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer. Screening tests are also available for lung and prostate cancer, but the recommendations are limited to individuals at higher risk.

Screening guidelines are typically based on age, sex at birth (which is relevant for the presence of certain organs), and personal cancer risk. In the following paragraphs we will use the term “men” and “women” to refer to sex assigned at birth and/or the presence of specific organs that may be affected by cancer. Just as cars need more attention as they age, as we get older our bodies require more frequent monitoring, as most cancer risk increases with age. However, not all cars need the same care: older cars need more frequent emissions tests, for example – at least, according to my mechanic! In a similar way, different bodies may need different care.

Let’s now take a closer look at the most widely recommended cancer screenings.

Breast cancer screening

Breast cancer screening and increased awareness, together with better treatment, have played a key role in increasing patient survival2. The 5-year survival rate – the percentage of patients alive 5 years after the diagnosis – shows how important early detection is for breast cancer: if found early, thus localized without spreading to distant organs, the survival rate is above 99%, while in distal stage, when cancer has spread to distant parts of the body like lungs, liver or bones, the survival rate is 32%3.

Recommendation for women at medium risk

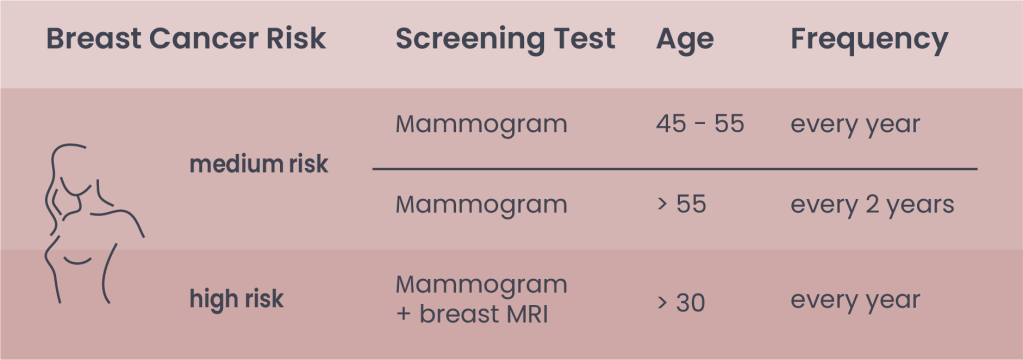

The recommendation on when to start, the frequency of screening, and the specific tests performed depend on our personal “breast cancer risk” (Table 1). A woman is considered at average risk for breast cancer, when:

- She does not have a personal history or a strong family history of breast cancer (multiple first-degree relatives- like parents, siblings, or children – with breast cancer),

- She does not have a genetic mutation known to increase risk of breast cancer (such as in the BRCA gene),

- She has not done chest radiation therapy before the age of 30.

Recommendation for women at high risk

The American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends a yearly mammogram and breast Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) starting at age 30 for women at high risk for breast cancer.

A person is considered at high risk for breast cancer if:

- Has a known BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation (based on genetic tests),

- Has a first-degree relative with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation, and has not had genetic testing themselves,

- Had radiation therapy to the chest before the age of 30,

- Has one of the including syndromes or has first-degree relatives with one of these syndromes: Li-Fraumeni syndrome, Cowden syndrome, or Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome.

While routine screening mammograms are not typically recommended for men, who rarely develop breast cancer (about 1% in the U.S.)4, those with a strong family history of breast cancer, a BRCA1/2 mutation, or other risk factors should discuss screening options with their doctor.

Mammogram

Breast cancer screening uses a low dose X-ray imaging technique called mammogram to check the breasts for signs of cancer. It can find cancers that are too small to be felt by touch. Mammography is currently the only screening method that has been proven to help prevent death from breast cancer. However, even mammograms are not perfect and do not find all breast cancers, and that is why it is important to participate in screening regularly.

Could mammograms be dangerous?

X-rays have the potential to cause cancer. Mammograms require small doses of radiation, so the risk of harm from this radiation exposure is low. As of now, the current data says that the benefits of mammography screening in organized programmes outweigh the potential harm from the radiation exposure. cite?

The risk of missing cancer during screening depends on the woman’s age and the density of her breasts, which is usually higher for younger women as breast tissue is usually denser before menopause. Dense breasts can also increase the risk of false positive tests. In these cases mammograms can be complemented with other tests, such as ultrasounds and biopsy.

In recent years, a new type of mammogram called digital breast tomosynthesis (known as three-dimensional [3D] mammography) has become more common for screening. The 3D mammogram allows for the visualization of breast tissue more clearly in three dimensions, while during regular mammograms the image of the breast is “flattened” in two dimensions.

Studies suggest this improvement may reduce the need for follow-up tests and detect more cancers, especially in women with dense breasts5. However, 3D mammograms are not currently available everywhere, can be more expensive, and insurance may not always cover the extra cost.

Breast ultrasound

This technique uses sound waves that reflect off the breast tissue to create detailed images of the breast. It’s especially helpful for younger women with dense breasts, where mammograms may not clearly show abnormalities. Ultrasound can provide a closer look at areas that appear suspicious on a mammogram and can help distinguish between fluid-filled cysts (usually not cancer) and solid masses (which may need further testing).

It’s also commonly used to guide a biopsy needle to collect cells from a specific area, including swollen lymph nodes under the arm. Ultrasound is widely available, doesn’t use radiation, is relatively easy to perform, and often costs less than other tests. While it’s a valuable tool alongside mammography, it’s not a replacement – as ultrasound may miss small details like microcalcifications that a mammogram can detect.

Table 1. Indications for breast cancer screening according to ACS

Note: After 40, women have the option to start screening with a mammogram every year. Mammogram tests can be integrated with ultrasound, especially in premenopausal women. In most European countries, mammograms are generally recommended every two years from age 45-75 (European Commission Initiative on Breast Cancer)

Breast Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Breast MRI is a medical imaging technique that takes advantage of radio waves and strong magnets to create detailed images of the breast and is used alongside mammograms for better detection.

Cervical cancer screening

Cervical cancer screening is probably one of the most successful stories of cancer secondary prevention. Once upon a time, cervical cancer was one of the leading causes of cancer death for American women6. Since the 1950s, the death rate has dropped as much as 70%, largely thanks to the widespread use of the Pap (Papanicolaou) screening test7. Similarly, a systematic review of European countries showed a reduction in mortality of 41% to 92% among women who participated in screening programs8. However, cervical cancer remains the leading cause of cancer death among women in 37 low- and middle-income countries where screenings are less available7.

It’s important to note that cervical cancer screenings are not a test for cancer itself. Pap-tests detect early cellular changes that may lead to cancer, while human papillomavirus (HPV) tests identify the presence of HPV, the primary risk factor for cervical cancer, found in 99.7% of cases worldwide9, 10. While almost 100% of cervical tumors are associated with HPV, an HPV infection does not necessarily mean a person will develop cancer. In fact, in about 90% of cases our immune system clears the infection within 2 years,11. However, persistent infections – especially with some HPV strains considered high-risk – can be dangerous. HPV is a big group of more than 200 viruses and 12 of them are considered “high-risk”, as they can cause different types of cancer, including cervical cancer. Among the high-risk HPV types 16 and 18 cause most HPV-related cancers12. Luckily now we have effective tools to detect them (Table 2)! Regular participation in organized screening programs can reduce the risk of invasive cervical cancer by up to 90%, using either of the two recommended screening tests (or a combination of both).

Pap (Papanicolaou) test

The Pap-test (or Pap-smear) is the oldest and most widely used screening method. It involves collecting cells from the cervix (the lower part of the uterus) and examining them under a microscope to check for abnormalities. If changes are found, follow-up tests may include colposcopy – an exam that looks closely at the cervix with a special magnifying instrument – and a HPV test.

HPV test

This newer test detects the presence of DNA from high-risk HPV types. A positive result doesn’t necessarily mean a cancer diagnosis, but it does indicate the need for closer follow-up, such as a colposcopy and/or biopsy. HPV test is performed with a lower frequency, since it looks for the virus itself, while Pap-tests look for cell changes caused by the virus. This means HPV tests can catch potential problems earlier, reducing the need for frequent screenings.

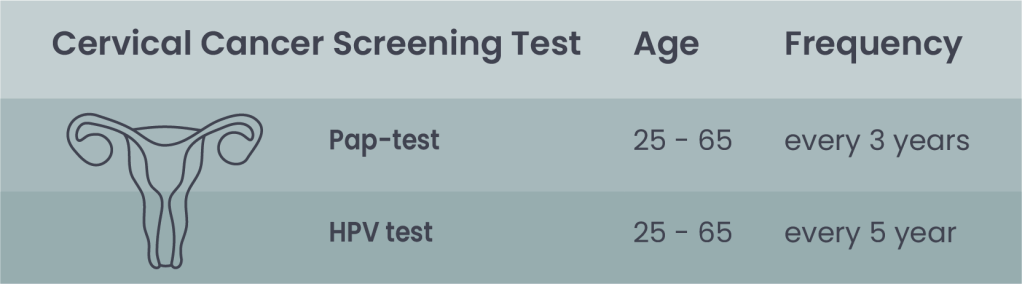

Table 2. Indication for cervical cancer screening according to ACS: The two screening tests can be performed as co-test or individually.

Note: In many European countries, Pap-test is recommended starting at age 25, but HPV test starting at age 30 to reduce overdiagnosis.

Who should get screened and when?

Health authorities in the U.S. and Europe recommend starting cervical cancer screening at age 25. Testing earlier is generally not advised, as HPV infections are very common in young, sexually active people and are often cleared naturally by the immune system. Early testing could lead to unnecessary follow up treatment and cause overdiagnosis.

Epidemiological studies show that after age 65, the risk of developing cervical cancer is low, especially for those who have had consistently negative test results in the past. It is important to remember that also those who have been vaccinated against HPV should still follow these guidelines for their age groups, as the vaccine can only protect against certain types of HPV, and there is still a chance of exposure to the virus before the vaccine.

Special Considerations

People who have had a total hysterectomy (removal of the uterus and cervix) can stop screening unless the surgery was done to treat cervical cancer or a serious pre-cancer.

Those at higher risk, such as individuals with weakened immune systems (due to HIV, organ transplant, or long-term steroid use), may need more frequent screening and should follow the advice of their healthcare provider.

Colon cancer screening

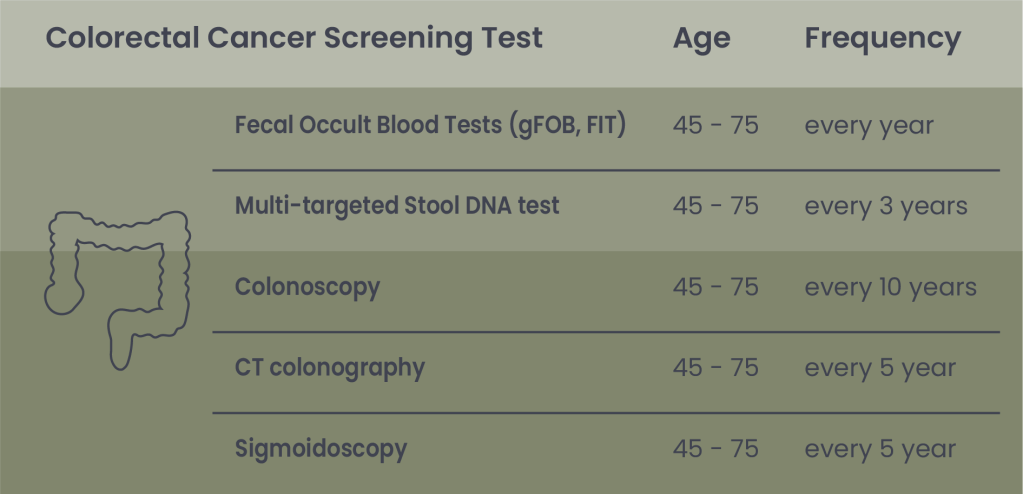

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the 3rd most common type of cancer worldwide in both men and women13. Luckily, we now have a wide variety of effective screening tools. Colonoscopy, the gold standard of CRC screenings, has been shown to reduce new cases by up to 69% and lower mortality by up to 88%14. Different screening tests (Table 3) have unique benefits and limitations but as the ACS emphasizes, “the most important thing is to get screened, no matter which test you choose15.” Your doctor can help you decide which option is best for you.

Stool-Based Tests: When your waste holds clues

Fecal occult blood tests (FOBT) detect small amounts of hidden (occult) blood in the stool – a possible sign of colorectal cancer or polyps, which are abnormal tissue growth in the bowel that can sometimes turn into cancer. Blood vessels in polyps or in cancers are often fragile and easily damaged when stool passes through, and can lead to a small bleeding which may not be visible to the naked eye, but can be detected by FOBT.

Stool-based tests are convenient – samples can be collected in the comfort of our home using a kit from the healthcare provider. However, compared with visual exams, they must be repeated more often because of their lower sensitivity and specificity. Blood in the stool may also result from other conditions like hemorrhoids or ulcers. If results are abnormal, a follow-up colonoscopy is needed to clarify the issue.

There are two types of FOBT16, which differ in stool sample collection and analysis.

- The guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) finds occult blood in the stool from the whole gastrointestinal tract through a chemical reaction. Some foods or drugs can affect the results of this test, so you could be instructed to avoid some medications (such as ibuprofen, that can irritate the gut and cause a false positives results), Vitamin C (which could interfere with the reaction and cause a false negative results), and red meat (which may contain some proteins from red blood cells and cause a false positive results) the week before the test. Multiple samples from different stools are typically required.

- The fecal immunochemical test (FIT) is a more recent test that detects blood specifically from the lower intestine. FIT does not have any drug or dietary restrictions as medication or foods do not affect the test results. Sample collection from one bowel movement is generally sufficient for this test.

Stool samples can be also used for Multi-targeted stool DNA or RNA tests with FIT, to look for certain mutations from cancer cells, as well as for occult blood. This test can be performed every 3 years, although the test for RNA changes has not yet been evaluated for inclusion in colorectal cancer screening guidelines.

Visual examinations: a look inside

Visual screening tests examine the inside of the colon and rectum for abnormalities using a scope, a tube-like instrument with a light and tiny video camera at the end, or with special imaging tests. They require bowel preparation beforehand to empty and clear the intestine for a better view.

There are three main visual exams:

Colonoscopy

A colonoscopy uses a camera attached to a thin, flexible tube to examine the entire colon. It can detect changes caused by cancer, polyps, and other diseases. Suspicious areas can be biopsied or removed during the procedure. It is the most thorough screening method.

CT colonography (virtual colonoscopy)

This test uses x-rays and a computed tomography (CT scan) technique to produce 3D-images of the colon and rectum. It is less invasive and doesn’t require sedation, though a small tube is placed in the rectum to inflate the colon with air or carbon dioxide for better images. The procedure is quick (about 15 minutes), but it still requires full bowel preparation. If abnormalities are found, a colonoscopy is needed for further evaluation or removal.

Table 3. Indication for Colorectal cancer screening according to the ACS

Note: In 2021, due to rising CRC rates in younger adults, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) lowered the starting age for screening from 50 to 45. For adults aged 76 to 85, the decision to screen should be based on individual health, life expectancy, screening history, and personal preferences.

Sigmoidoscopy

This test examines only the lower portion of the colon and is quicker and easier than a full colonoscopy. It requires a less intense bowel preparation and no sedation. However, because at least 40% of colorectal cancers start in the upper colon, this test is less commonly used in the U.S. If polyps or cancer are found, a full colonoscopy will be required to assess the rest of the colon.

Blood-based test

There are two FDA-approved blood tests for colorectal cancer screening – Shield and ColoHealth – which detect DNA changes in cells present in the blood that may indicate cancer or pre-cancer. However, they are not currently included in the American Cancer Society’s and in the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) screening guidelines.

Not all cancers can be prevented, but some can be caught early. Following screening recommendations is one of the most effective ways to protect your health. Don’t wait for symptoms – taking care of your body means knowing when your “maintenance light” comes on, so you can schedule the recommended screenings and make secondary prevention a regular part of your life.

Information about insurance coverage for cancer screenings in the U.S. can be found here.

You can find more information about:

Breast cancer screening here

Cervical cancer screening here

Colorectal cancer screening here.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (n.d.), Client (Patient) Reminder Planning Guide. cdc.gov. Retrieved May 5th 2025 from https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/php/ebi-planning-guides/client-reminder-planning-guide.html. ↩︎

- Goddard KAB, Feuer EJ, Mandelblatt JS, et al. Estimation of Cancer Deaths Averted From Prevention, Screening, and Treatment Efforts, 1975-2020. JAMA Oncol. 2025;11(2):162–167. ↩︎

- American Cancer Society. (16 January 2025), Survival Rates for Breast Cancer. Cancer.org. Retrieved May 4th 2025 from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/understanding-a-breast-cancer-diagnosis/breast-cancer-survival-rates.html. ↩︎

- Woods RW, et. all., Image-based screening for men at high risk for breast cancer: Benefits and drawbacks. Clin Imaging. 2020 Mar;60(1):84-89. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2019.11.005. Epub 2019 Nov 28. PMID: 31864206; PMCID: PMC7242122. ↩︎

- American Cancer Society. (14 January 2022), Mammogram Basics. Cancer.org. Retrieved May 5th 2025 from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/screening-tests-and-early-detection/mammograms/mammogram-basics.html. ↩︎

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (3 March 2025), Cancers Caused by HPV. cdc.gov. Retrieved May 13 2025 from https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/about/cancers-caused-by-hpv.html. ↩︎

- American Cancer Society. (29 July 2024), Sandy McDowell. Cervical Cancer Leads Cancer Deaths for Women in 37 Countries. Cancer.org. Retrieved May 8th 2025 from https://www.cancer.org/research/acs-research-news/cervical-cancer-leads-cancer-deaths-37-countries.html. ↩︎

- E.E. Jansen, N. Zielonke, A. Gini, A. Anttila, N. Segnan, Z. Vokó, et al. Effect of organised cervical cancer screening on cervical cancer mortality in Europe: a systematic review. European Journal of Cancer, 127 (2020), pp. 207-223 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2019.12.013. ↩︎

- Walboomers JM, et all.,. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999 Sep;189(1):12-9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. PMID: 10451482. ↩︎

- Alrefai EA, Alhejaili RT, Haddad SA. Human Papillomavirus and Its Association With Cervical Cancer: A Review. Cureus. 2024 Apr 1;16(4):e57432. doi: 10.7759/cureus.57432. PMID: 38699134; PMCID: PMC11063572. ↩︎

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (3 July 2024), About HPV. cdc.gov. Retrieved May 13 2025 from https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/about/index.html. ↩︎

- NIH National Cancer Institute (9 May 2025), HPV and Cancer. cancer.gov Retrieved May 13 2025 from https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-and-cancer. ↩︎

- Cancer TODAY | IARCInternational Agency for Research on Cancer (2 August 2024), Absolute numbers, Incidence and Mortality, Both sexes. gco.iarc.who.int. Retrieved May 13 2025 from https://gco.iarc.fr/today/en/dataviz/bars?types=0_1&mode=cancer&group_populations=1&sort_by=value1&key=total. ↩︎

- Ladabaum, Uri et al. Strategies for Colorectal Cancer Screening Gastroenterology, Volume 158, Issue 2, p418-432 January 2020. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.06.043. ↩︎

- American Cancer Society. (28 February 2025). Colorectal Cancer Screening Tests. Cancer.org. Retrieved May 5th 2025 from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/screening-tests-used.html. ↩︎

- Tinmouth J, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Allison JE. Faecal immunochemical tests versus guaiac faecal occult blood tests: what clinicians and colorectal cancer screening programme organisers need to know. Gut. 2015 Aug;64(8):1327-37. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308074. Epub 2015 Jun 3. PMID: 26041750. ↩︎

© 2025 WithinOncology. All rights reserved.

This article, including all text, tables, and figures, is the intellectual property of WithinOncology and its contributors. Unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or use of any content without explicit written permission is strictly prohibited. For inquiries, please contact us via the contact form.

Leave a reply to Laura Mainz Cancel reply