Prevention

Primary | Secondary | Tertiary |

Why it matters and how much

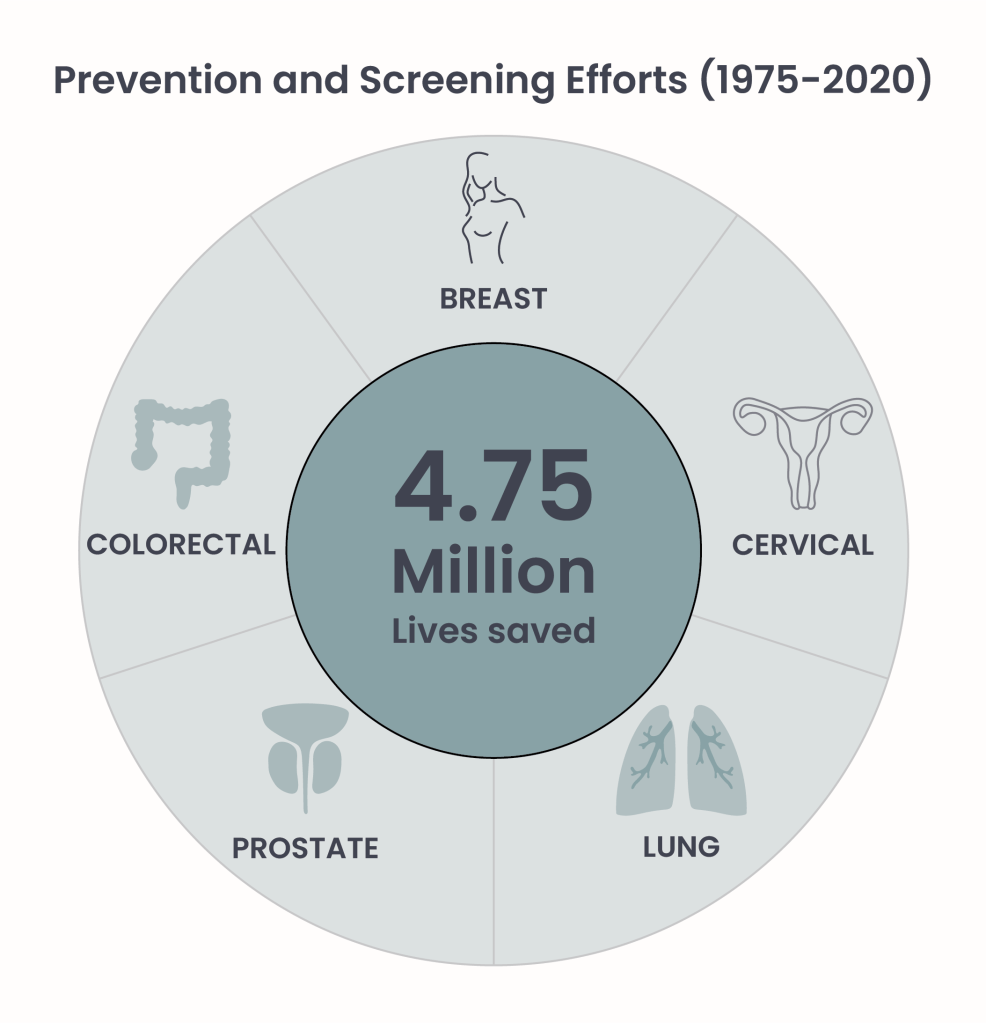

Figure 1.

Cancer is a multifaceted disease whose development is influenced by a mixture of genetic and environmental factors. While we have little control over the genetic factors – the information written in our DNA – we can influence environmental factors through our behavior. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), prevention offers the most cost-effective long-term strategy for controlling cancer, with costs that are not only financial but also measured in human lives. In essence, cancer prevention encompasses every action aimed at reducing the risk of developing cancer and mitigating its impact if already present. Those actions can be very powerful, as it has been estimated that between 30–50% of all cancer cases are preventable1.

A recent model-based study2 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) evaluated the impact of prevention, screening, and treatment interventions on five types of cancer: breast, cervical, colorectal, lung, and prostate. These cancers are among the leading causes of cancer-related deaths, and established strategies exist for their prevention, early detection, and treatment. The findings indicate that cancer prevention and screening were the primary contributors to reducing mortality from these five cancers over the past 45 years (Figure 1).

Identifying the preventable causes of cancer

As cancer is not a single disease, but a group of related diseases, there are many factors in our lifestyle and the environment that may increase or decrease our risk of getting one of the several types of cancer. Thus, the first step in cancer prevention is to identify its modifiable causes. The leading global resource for identifying cancer hazardous agents is the Monographs Programme led by The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC)3. In this program, a working group of independent international experts evaluates the potential carcinogenicity – meaning ability of causing cancer – of different agents like:

- chemicals (e.g. formaldehyde, benzene)

- physical agents (e.g. solar radiation)

- biological agents (e.g. viruses and bacteria)

- pharmaceuticals (e.g. chloramphenicol)

- complex mixtures (e.g. air pollution)

- occupational exposures (e.g asbestos, virus, pesticides)

- other factors (e.g. tobacco smoking, alcohol)

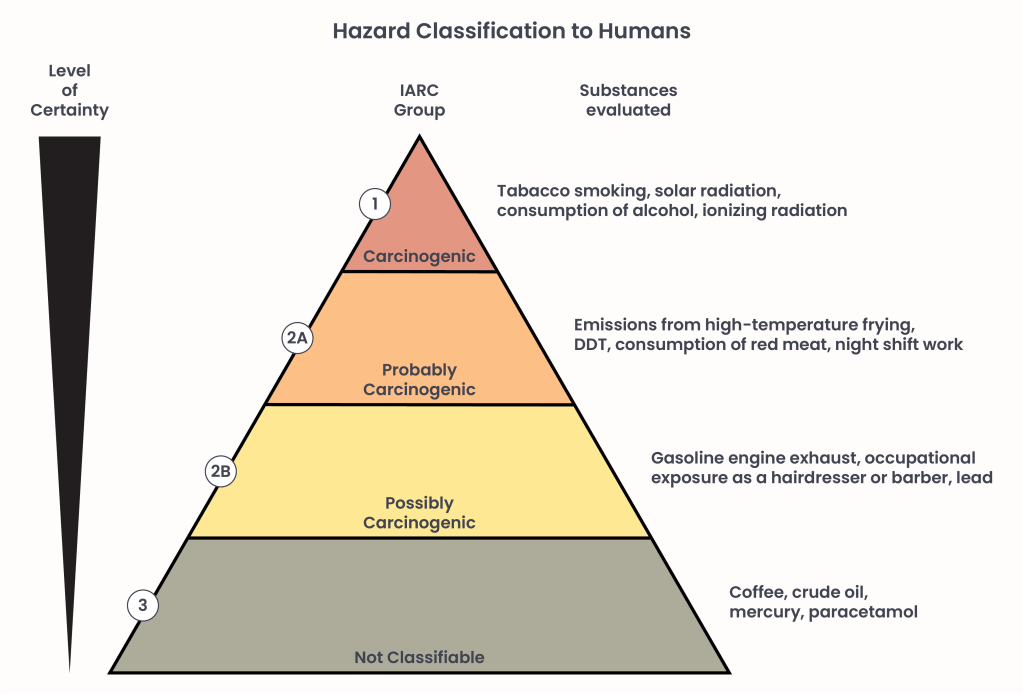

Since 1971, more than 1000 agents have been evaluated and classified into one of four categories, ranging from “known carcinogen to humans” (Group 1) to “not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans” (Group 3) (Figure2). The classification categories reflect the strength of evidence that an agent can cause cancer (“hazard”) – how sure we are that it causes cancer – but do not measure the likelihood of cancer occurring (“risk”) at a given exposure level. For example, substances in Group 2A are classified as “probably carcinogenic” because there is limited evidence of cancer in humans but sufficient evidence in animal models. In contrast, substances in Group 2B are considered “possibly carcinogenic” as the evidence in animal models is less than sufficient.

Figure 2.

Types of prevention

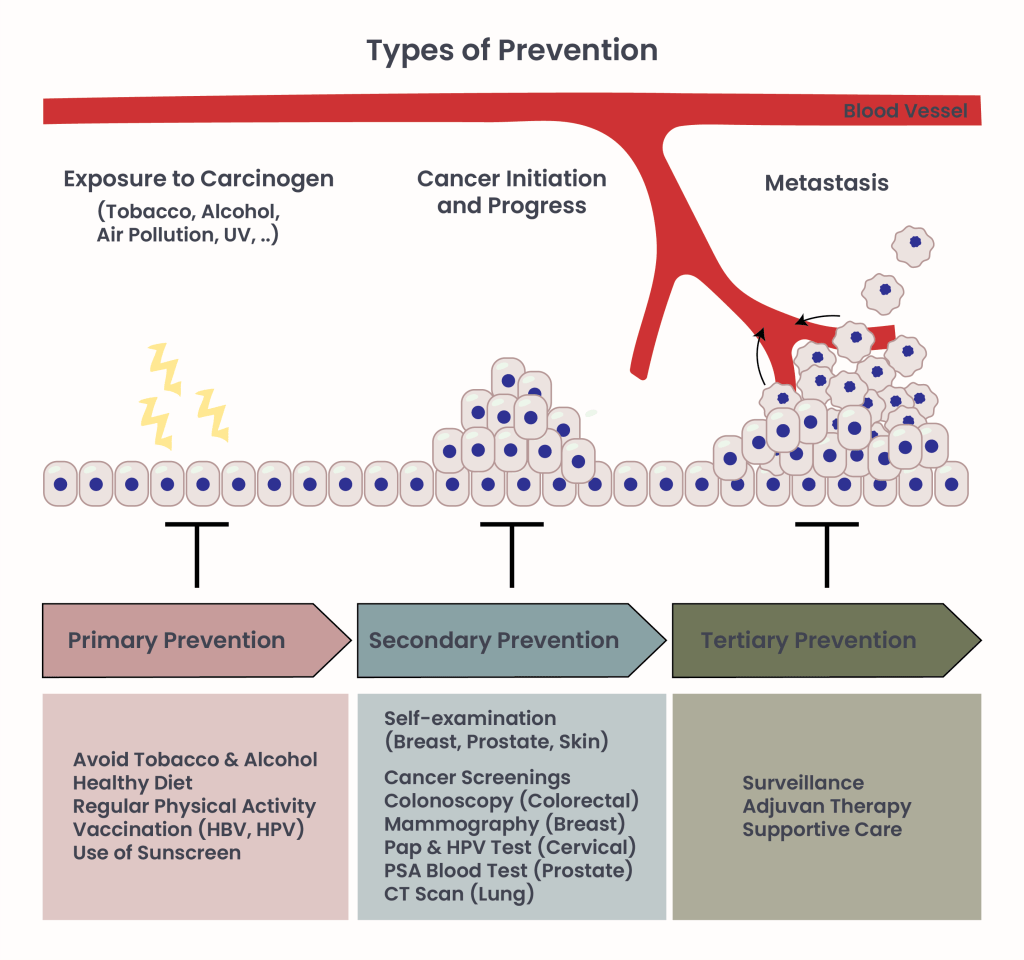

Cancer prevention can be divided in three levels (Figure 3):

Primary prevention

The first level of prevention aims to stop the disease before it occurs. Therefore, the first step in reducing the risk of cancer development is to avoid exposure to risk factors. Some well known and widespread cancer hazards include tobacco, obesity, alcohol, and ultraviolet radiation (UV). Thus, primary prevention strategies involve adopting healthy behaviors and lifestyles, such as maintaining a balanced diet, exercising regularly, avoiding smoking and alcohol consumption, and minimizing unprotected exposure to sunlight (UV). While these changes may be easier said than done, they are achievable – and as an additional bonus, they also have other positive effects on our health: they can reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and stress, and are generally associated with a longer life expectancy4.

Other cancer hazards can be found in our direct environment (like radon, asbestos and air pollution), thus raising awareness and taking measures to reduce exposure to these hazards are essential steps in prevention.

Additionally, certain viral infections can increase cancer risk. For example, hepatitis B virus (HBV) can lead to liver cancer, while human papilloma virus (HPV) is a major risk factor of cervical cancer, and has also been linked to cancers of the mouth, anus, and penis. The good news is that effective vaccines are available for both viruses, making vaccination a powerful tool for primary cancer prevention.

Secondary prevention

The second level of prevention aims to reduce the impact of a tumor that is already present – often silently. Much like wildfires, catching cancer early can reduce the damage done, by preventing it from spreading and getting out of control. Therefore, early detection is the key to improve treatment outcomes and can be achieved primarily through:

- Self examinations: Simple procedures that everyone can perform regularly to check for signs of cancer in different parts of the body. Indications exist for self-examination for breast 5, skin6 7 and testicular8 cancer.

- Screenings: Routine tests have been developed for the early detection of specific cancer types in the general population, including breast, cervical, colorectal, and prostate cancer. Additionally, lung cancer screening is available for individuals at high risk, such as smokers and former smokers.

But why not screen everyone if possible? Tests aren’t perfect. False positive (test determined cancer was present, but it was not) and false negative (test determined cancer is not present, but it was) diagnoses do occur. Research has shown that overdiagnosis and overtreatment can lead to adverse effects – both physically and psychologically9. Striking a balance is crucial: screening should be conducted when beneficial, but excessive testing can result in unnecessary procedures and the emotional toll of false alarms and unwarranted cancer diagnoses.

Tertiary prevention

The third level of prevention does not focus on preventing cancer itself but rather on minimizing its burden on cancer patients. It aims to improve the survivorship and quality of life after a cancer diagnosis.

Methods of tertiary prevention includes:

Supportive care: Measures to provide comprehensive care and support in managing the physical, psychological, and social effects of cancer and its treatments. This requires a multidisciplinary approach, which may include rehabilitation programs, psychological support, nutritional counseling, and assistance in managing treatment side effects10. Supportive care is offered by many non-profit organizations free of charge.

Surveillance and monitoring: Regular check-ups and screening to promptly detect cancer recurrence or the onset of a secondary tumor.

Adjuvant therapy: Treatments administered after the primary treatment of cancer, that can include chemotherapy, radiotherapy or hormonal therapy depending on the patient’s conditions. These therapies play a crucial role in prolonging progression-free survival (PFS) and thus overall survival (OS).

Progression free survival (PFS) measures how long patients with cancer live without their disease progressing or worsening.

Overall survival (OS) is the time from the start of treatment until the patient dies from any cause, regardless of whether their cancer has progressed.

Figure 3.

Note: Definitions of primary, secondary, and tertiary cancer prevention may vary; however, the core message of prevention remains consistent. Understanding the complexities of individual and population-level cancer risk, combined with a broad range of prevention strategies, empowers the whole community to play a crucial role in cancer prevention.

You can find more information about cancer prevention in the Within Prevention article series.

- World Health Organization.(n.d.), Preventing cancer. who.int. Retrieved March 17 2025 from https://www.who.int/activities/preventing-cancer. ↩︎

- Goddard KAB, Feuer EJ, Mandelblatt JS, et al. Estimation of Cancer Deaths Averted From Prevention, Screening, and Treatment Efforts, 1975-2020. JAMA Oncol. 2025;11(2):162–167. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2024.5381. ↩︎

- Samet et al., The IARC Monographs: Updated Procedures for Modern and Transparent Evidence Synthesis in Cancer Hazard Identification. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 2019. ↩︎

- MD Anderson Cancer Center; Kellie Bramlet (October 2016),The positive side effects of cancer prevention. mdanderson.org. Retrieved March 13 2025 from https://www.mdanderson.org/publications/focused-on-health/cancer-prevention-benefits.h31Z1590624.html. ↩︎

- National Breast Cancer Foundation; revised by Lillie D. Shockney ( 6 Jan. 2025), Breast Self-Exam. nationalbreastcancer.org. Retrieved March 14 2025 from http://nationalbreastcancer.org/breast-self-exam/. ↩︎

- American Cancer Society. (26 June 2024), How to Do a Skin Self-Exam. cancer.org. Retrieved March 14 2025 from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/risk-prevention/sun-and-uv/skin-exams.html. ↩︎

- American Academy of Dermatology Association (n.d.), What to look for: ABCDEs of melanoma. aad.org. Retrieved March 10 2025 from https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/skin-cancer/find/at-risk/abcdes. ↩︎

- John Hopkins Medicine; Nirmish Singla, M.D., M.Sc.(n.d.) How to Perform a Testicular Self-Exam. hopkinsmedicine.org. Retrieved March 15 2025 from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/testicular-cancer/how-to-perform-a-testicular-selfexam-advice-from-urologist-nirmish-singla. ↩︎

- Loomans-Kropp, H.A., Umar, A. Cancer prevention and screening: the next step in the era of precision medicine. npj Precision Onc 3, 3 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-018-0075-9. ↩︎

- Jacobsen, P. B., & Andrykowski, M. A. (2015). Tertiary prevention in cancer care: Understanding and addressing the psychological dimensions of cancer during the active treatment period. American Psychologist, 70(2), 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036513. ↩︎

Reviewed. 03/2025