Multiple Myeloma 101

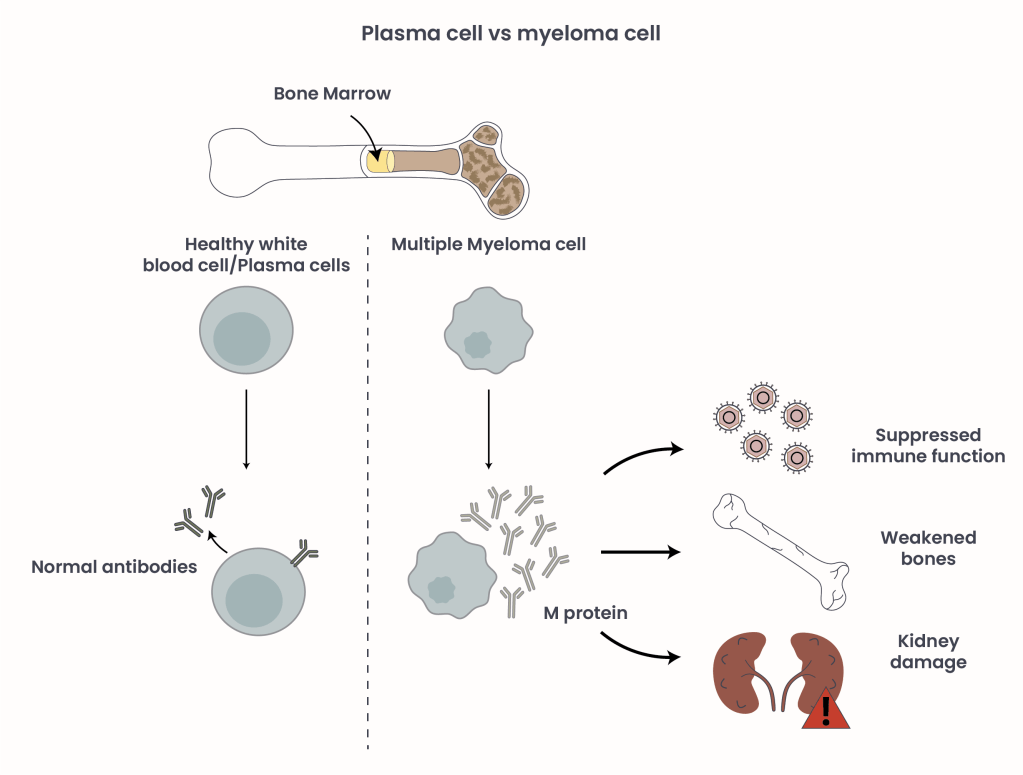

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a type of blood cancer that originates in the bone marrow – the soft, spongy tissue at the center of bones where blood cells are produced1. MM arises when normal plasma cells, a type of white blood cell responsible for producing antibodies, accumulate genetic mutations and transform into malignant MM cells. These abnormal cells proliferate uncontrollably, crowding out healthy blood cells and forming tumors in the bone marrow known as plasmacytomas. Unlike normal plasma cells that produce a variety of antibodies to fight infections, myeloma cells secrete large quantities of a single, ineffective antibody called monoclonal (M) protein. This excess M protein accumulates in the body, leading to complications such as kidney damage and hyperviscosity (thickened blood). Additionally, the M protein can weaken bones, causing pain and fractures, and suppress immune function, increasing the risk of serious infections (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Plasma cells in comparison to malignant myeloma cells and their effect on health and disease.

While MM remains incurable, advances in treatment have shifted care from conventional chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation to more modern therapies, allowing many patients to manage the disease as a chronic condition with extended survival. However, all patients relapse earlier or later, meaning the cancer has returned, or become refractory, meaning the disease no longer responds to treatment. This stage, known as relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM), presents significant treatment challenges, particularly in patients with high-risk features such as aggressive disease or adverse genetic profiles, a specific combination of genetic mutations known to have an increased risk for disease progression, poor treatment response or severe outcomes.

T-cell engagers – a new tool in the MM treatment arsenal

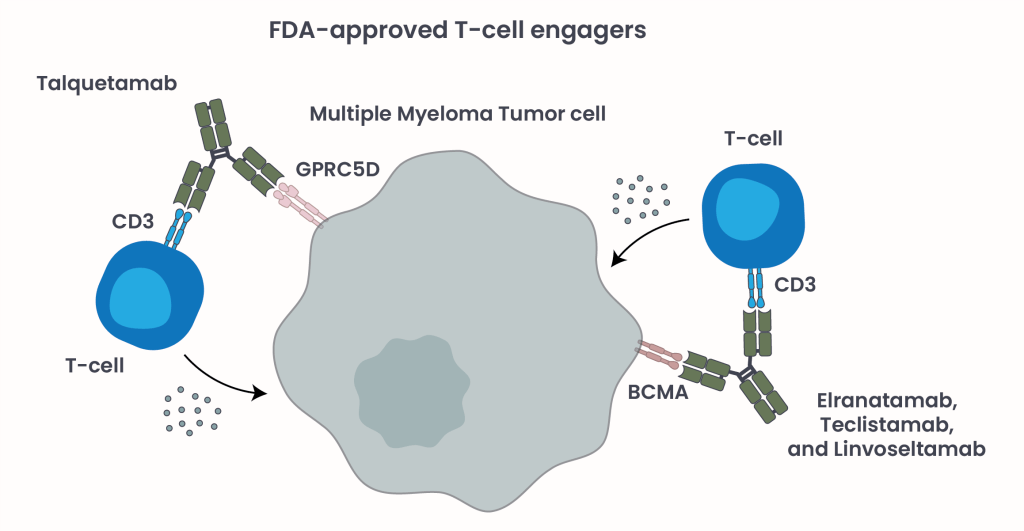

As our understanding of MM biology has advanced, so too has the development of novel promising therapies designed to leverage the body’s immune system – most notably, T-cell redirecting therapies2, 3. These immunotherapies take advantage of the body’s immune system to target and eliminate cancer cells. One such class includes T-cell engagers (TCEs), a class of bispecific antibodies (BsAbs) designed to bring T-cells into close proximity with myeloma cells, triggering targeted cell death (Figure 2). Unlike Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cells, another T-cell redirecting therapy used as late line treatment for RRMM patients, TCE BsAbs are off-the-shelf agents allowing for a substantially shorter time between treatment decision and treatment initiation.

Figure 2. FDA-approved TCE BsAbs and their mechanism of action.

TCE BsAbs are called “bispecific” because they contain two binding sites: one binds T-cells via their CD3 receptors, and the other links to myeloma cells by binding to a tumor-associated antigen such as B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) or G protein-coupled receptor class C group 5 member (GPRC5D) present on their surface. This interaction forms a “molecular bridge” that activates the T-cells to release toxic molecules, killing the tumor cells (Figure 2).

TCE BsAbs have proven to be very effective, but can also cause immune-related side effects, including, but not limited to2:

- Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS): A systemic inflammatory response caused by a rapid release of cytokines, small signaling proteins that act as messengers for the immune system. Symptoms range from fever and fatigue to life-threatening organ dysfunction. Primary interventions are anti-fever medications and intravenous hydration.

- Immune Effector Cell-Associated Neurotoxicity Syndrome (ICANS): A reversible neurological side effect caused by activated immune cells entering the brain, causing inflammation, leading to symptoms ranging from confusion and headaches to seizures or coma. Primary intervention is the application of dexamethasone, a potent steroid medication, to decrease inflammation and slow down the overactive immune system.

FDA-approved TCE BsAbs in Multiple Myeloma

Currently, four TCE BsAbs have received FDA approval for the treatment of RRMM. These include BCMA-targeting Teclistamab4, Elranatamab5, and Livoseltamab6; and GPRC5D-targeting Talquetamab7 (Table 1). These targets were selected based on their abundance in multiple myeloma. BCMA is a membrane protein crucial for plasma cell survival, but is found at significantly higher levels on myeloma cells compared to normal plasma cells. GPRC5D, another therapeutic target, is a receptor that is highly expressed on myeloma cells but largely absent in healthy B-cells and tissues, making it an attractive and specific marker for targeted therapy.

Despite patients in these trials being heavily pretreated, often having exhausted multiple prior therapies representing a high resilience of the cancer cells to adapt and become resistant to treatments, all four agents have shown strong clinical activity. Their overall response rates (ORRs), a measure indicating the percentage of patients whose tumor cells shrink or disappear after treatment, range from 33% to 73%, highlighting their potential to deliver meaningful responses in a population with limited treatment options.

| TECVAYLI (Teclistamab)4 | ELREXFIO (Elranatamab)5 | TALVEY (Talquetamab)7 | LYNOZYFIC (Livoseltamab)6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Janssen Biotech, Inc. | Pfizer, Inc. | Janssen Biotech, Inc. | Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. |

| Target | BCMA x CD3 | BCMA x CD3 | GPRC5D x CD3 | BCMA x CD3 |

| FDA-approval | October 2022 | August 2023 | August 2023 | July 2025 |

| Clinical trial resulting in approval | MajesTEC-1 study (NCT04557098) (single-arm, open label, multi-center phase 1/2 study) | MagnetisMM-3 study (NCT04649359) (single-arm, open-label, non-randomized, multicenter phase 2 study) | MonumenTAL-1 study (NCT03399799) (single-arm, open-label, multicenter phase 1/2 study) | LINKER-MM1 study (NCT03761108) (open-label, multicenter, multicohort phase 1/2 study) |

| Participants characteristics | – RRMM patients who have received at least three prior lines of treatments – 110 patients, – median age of 66 years (only enrolled patients that never had a BCMA-directed therapy (=BCMA-naive) | – RRMM patients who have received at least four prior lines of treatments Cohort A: – BCMA-directed therapy-naive patients – 123 patients, – median age of 69 years Cohort B: – BCMA-directed therapy-exposed patients – 64 patients – median age of 68 years | – RRMM patients who have received at least three prior lines of treatments Cohort A: – T-cell redirected therapy-naive patients – 100 patients received treatment once weekly – 87 patients received treatment once every two weeks – median age of 67 years Cohort B: – T-cell redirected therapy-exposed patients – 32 patients received treatment once weekly – median age of 61 years | – RRMM patients who have received at least four prior lines of treatments – 80 patients – median age of 71 years |

| Overall response rate | 61.8% | Cohort A 57.7% Cohort B 33.3% | Cohort A 73.6% Cohort B 72% | 70% |

| Cytokine Release Syndrome | – 72% total – 50% grade 1, 21% grade 2, 0.6% grade 3 – median time to onset was 2 days – median duration was 2 days – step-up dosing schedule to reduce risk – fewer incidences with each dose | – 58% total – 44% grade 1, 14% grade 2, 0.5% grade 3 – median time to onset was 2 days – median duration was 2 days – step-up dosing schedule to reduce risk – fewer incidences with each dose | – 76% total – 57% grade 1, 17% grade 2, 1.5% grade 3 – median time to onset was 27 hours – median duration was 17 hours – step-up dosing schedule to reduce risk | – 46% total – 35% grade 1, 10% grade 2, 0.9% grade 3 – median time to onset was 11 hours – median duration was 15 hours – step-up dosing schedule to reduce risk – fewer incidences with each dose |

| Neurological toxicity (including ICANS) | – 57% total – 2.4% grade 3 and 4 – ICANS: 6% – median time to onset was 4 days – duration was 3 days | – 97% total – 7% grade 3 and 4 – ICANS: 3.3% – median time to onset was 3 days – duration was 2 days | – 55% total – 6% grade 3 and 4 – ICANS: 9% – median time to onset was 2.5 days – duration was 2 days | – 54% total – 8% grade 3 and 4 – ICANS: 8% – median time to onset was 1 day – duration was 2 days |

Table 1. Comparison of FDA-approved TCE BsAbs for MM. Severity grading is defined as grade 1 mild, grade 2 moderate, grade 3 severe, grade 4 life-threatening, and grade 5 death.

Resistance to treatment

Despite being a promising therapeutic approach for MM patients, TCE BsAbs are not universally effective3. Approximately one-third of patients exhibit primary resistance, meaning they do not respond to treatment initially. Others may initially respond but eventually develop resistance over time. This challenge is particularly pronounced in patients with late stage and/or extramedullary disease (EMD), a condition in which MM cells spread beyond the bone marrow into soft tissues or organs such as the liver, lungs, or skin forming plasmacytomas. These patients typically experience poorer outcomes with TCE BsAbs therapy, so late stage and EMD are used as predictive factors of response.

Resistance to TCE BsAbs can emerge through several mechanisms3. In some cases, tumor cells adapt by losing the specific antigen that the bispecific antibody targets, rendering the therapy ineffective. Another common issue is T-cell exhaustion, a state in which T-cells lose their toxic function due to prolonged activation, diminishing their ability to eliminate cancer cells effectively.

To overcome these barriers, ongoing clinical trials are investigating combination treatment strategies3. These include pairing two different TCE BsAbs, or combining them with other immunotherapies or targeted therapies. The goal is to enhance the depth and durability of response, especially in patients with high-risk or resistant disease.

Conclusion

TCE BsAbs represent a transformative option for patients with RRMM, particularly those who have exhausted standard therapies. As off-the-shelf, immune-based treatments, they offer rapid, potent responses by redirecting the body’s own T-cells to attack tumor cells. Continued research will explore the possibility of earlier integration in patients’ disease management, mitigate toxicities, and overcome resistance – further extending survival and improving quality of life for patients with multiple myeloma.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (Version 2025), Guidelines for patients. https://www.nccn.org/home. Retrieved January 3 2026 from https://www.nccn.org/patientresources/patient-resources/guidelines-for-patients. ↩︎

- Albayrak G, Wan PK, Fisher K, Seymour LW. T cell engagers: expanding horizons in oncology and beyond. Br J Cancer. 2025 Nov;133(9):1241-1249. doi: 10.1038/s41416-025-03125-y. Epub 2025 Jul 23. PMID: 40702106; PMCID: PMC12572156. ↩︎

- Cirstea D, Puliafito B, Kim BE, Lei M, Raje N. Bispecific T-cell engager therapy for multiple myeloma. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2025 Sep;38(3):101649. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2025.101649. Epub 2025 Aug 5. PMID: 40915704. ↩︎

- Janssen Biotech, Inc. (Sep. 2025), Choose TECVAYLI. https://www.jnj.com. Retrieved January 3 2026 from https://www.tecvaylihcp.com. ↩︎

- Pfizer, Inc. (n.d.), DISCOVERY THE DEPTHS OF DURABLE RESPONSE. https://www.pfizerpro.com. Retrieved January 3 2026 from https://elrexfio.pfizerpro.com. ↩︎

- Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (n.d.), DISCOVERY LYNOZYFIC. https://www.regeneron.com. Retrieved January 3 2026 from https://www.lynozyfichcp.com. ↩︎

- Janssen Biotech, Inc. (Oct. 2025), EVOLVE YOUR STRATEGY WITH TALVEY. https://www.jnj.com. Retrieved January 3 2026 from https://www.talveyhcp.com. ↩︎

© 2025 WithinOncology. All rights reserved.

This article, including all text, tables, and figures, is the intellectual property of WithinOncology and its contributors. Unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or use of any content without explicit written permission is strictly prohibited. For inquiries, please contact us via the contact form.

Leave a comment