When art imitates life

Figure 1. Innate and adaptive immunity make up two halves of the immune system which interact to achieve the desired responses. Innate immune cells, some of which are depicted here, rapidly respond to infection, whereas adaptive immune responses gradually build following infection. B- and T-cells, two of the most common adaptive immunity cells, are depicted here. These cells can form immune memory against specific antigens, so that future responses are faster, as well as direct on-going immune responses, and directly kill invading cells.

An orchestra of unique cell types works in harmony to allow our immune system to sort out invading threats such as bacteria, viruses, and cancer. The immune system can be divided into two parts: the native, adaptive (Figure 1). All cells that do the work and make up the immune system are also known as white blood cells. Native immune system cells are considered the first line of defence and fight off foreign invaders like infections or cancer as they attempt to take hold and grow. The adaptive immune system consists of B- and T-cells, among other types. B-cells store memories of invading threats in the form of bespoke antibodies. They also release antibodies to neutralize invading threats directly, or through recruitment of other immune cells. T-cells (which are made in our bone marrow, and then mature in the thymus, thus the ‘T’) also learn from invaders to prepare for future encounters, direct the entire immune response, and are capable of killing invading cells1. Balance between the numerous components of the immune system is needed to rapidly fight foreign invaders without causing a cacophony of misdirected responses that could cause more harm than good. T-cells are the immune systems conductors, leading the fight against pathogenic or cancerous cells while coordinating the complex actions of their varied orchestra.

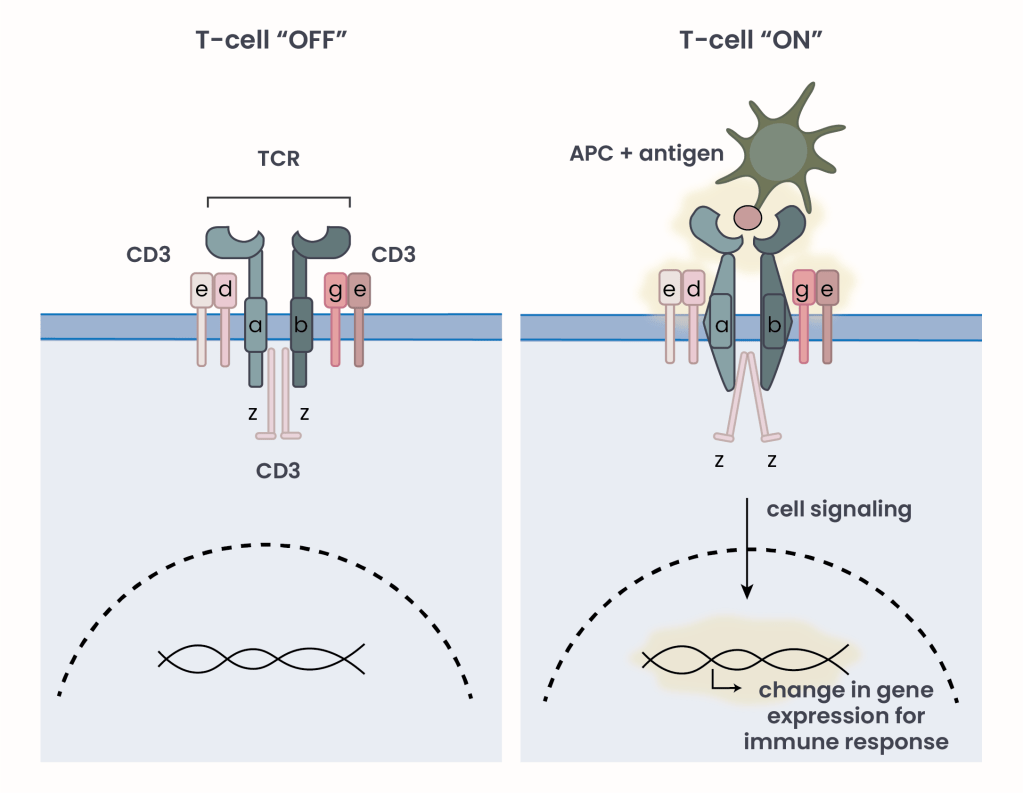

To coordinate many instruments, a conductor must be able to see and hear (apart from Beethoven), as well as respond and give cues to their musicians in the form of baton movements or animated facial expressions. In the case of T-cells, other molecules, or antigens, are sensed. Antigen presenting cells (APCs) take up molecules from invaders such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, or cancer cells, and present them as antigens to T-cells to generate a response. The response comes in changes in gene expression. The outcome is dependent on the particular molecule and the context in which it was sensed. Antigens are sensed through the T-cell receptor (TCR) complex (a sort of antenna), which uses the cluster of differentiation 3 (CD3) complex to send a message throughout the cell which signals for gene expression changes (Figure 2). The TCR-CD3 interaction allows T-cells to recognize, learn from, and respond to a vast array of unique signals.

How T-cells see: TCR

The TCR consists of two proteins, in 95% of T-cells these are α (alpha) and β (beta) (Figure 2, top), while the rest express similar proteins that serve slightly distinct functions. Most of the TCR lies outside of the cell, where the tips directly sense antigens presented by APCs. The antigen sensing tip of the TCR varies from cell to cell, allowing each T-cell to recognize different antigens. This heterogeneity, or diversity, gives our body the chance to respond to and learn from a large variety of threats. The membrane-adjacent part of the TCR is the signaling component that mediates interaction with CD3, and is constant between cells. When the variable sensing tip interacts with an antigen, it triggers a change in the shape of the constant region, which tells CD3 to send a message signaling for gene expression changes2.

How T-cells respond: CD3

CD3 is made of four unique proteins, ε (epsilon), ɣ (delta), δ (gamma), and ζ (zeta) (Figure 2, bottom) (Note: many protein subunits of large complexes are named by greek letters that distinguish one from another, but are distinct from subunits of other complexes with the same greeknames). These proteins combine pair-wise to form three unique sub-complexes, ε-δ, ε-ɣ, and ζ-ζ, which all work together to send the message that an antigen has been encountered and gene expression changes are needed3. CD3 proteins are also anchored to cell membranes, with critical signaling portions of each individual member located inside the cell. When the TCR activates CD3, a variety of proteins are recruited to the complex, resulting in a chain reaction of signaling. The outcome of these events is generally modulation of gene expression – but which genes are affected, and how they are affected, are dependent on the TCR, and the context2.

Figure 2. T-cells sense antigens through the T-cell receptor (TCR), and respond through cluster of differentiation 3 (CD3). When an antigen-presenting cell (APC) presents an antigen to a TCR on a T-cell, the T-cell gets turned “on.” The antigen-sensing tip of the TCR protein can vary from cell to cell, allowing for almost all antigens to be sensed. The nearby CD3 proteins then recruit specific proteins, which help to send a message through the cell that reaches the DNA in the nucleus. The message leads to changes in gene expression that facilitate both present and future immune responses.

Many factors are considered for single responses

Not all T-cells are the same. They can express a variety of TCRs, and even if there may be many T-cells that can sense the same antigen, they may do so with different strengths. Each T-cell expresses many copies of the TCR and CD3 complexes. The strength of the interaction between the TCR and antigen, and abundance of interaction across many TCRs in one T-cell, are key determinants of the strength and longevity of the response. As always, context is king. T-cells hone their response to antigens by integrating signals received from other immune cells, either directly, or indirectly through released messages in the form of proteins4. Specific actions that T-cells perform include dampening their response to allow for recovery from inflammation, proliferating in order to amplify their responses and/or form long-lasting immune memory, or changing their cellular identity to become a more specialized type of T-cell that can directly kill invading threats. These conductors listen to their orchestra and read the room, incorporating a myriad of signals into a clear message that calls for a specific response.

Types of T-cells

T-cells also vary based on their type, which is specified during maturation, and differs based on the expression of specific proteins, which affect responses4. T-cell identity can also change during immune responses. Of the many types, some of the most important are:

- CD4+ Helper T-cells: activate B-cells to produce antibodies, and stimulate CD8+ Cytotoxic cells.

- CD8+ Cytotoxic T-cells: directly destroy infectious or cancerous cells – sometimes the conductor has to get their hands dirty alongside their orchestra!

- regulatory T-cells (Tregs): “turn off” immune responses. They are critical for limiting inflammation after a regular response, but also for preventing our body from recognizing our own cells as a threat, also known as autoimmunity4.

All of these cell types express TCR and CD3, as well as their own unique proteins such as CD4 or CD8.

The immune system works throughout our body, and is involved in almost every single biological response. Entire therapeutic areas, including among cancer research, are focused on specific types of immune cells or their products, such as antibodies. It would not be an exaggeration to say that immunology is one of, if not the most complex yet exciting areas of biomedical research. T-cells are particularly important for health and disease, as they can respond to numerous cues through their TCR, integrate what they “see” with messages from other immune cells, and respond through CD3 to modify gene expression, and thus produce a response. T-cell responses can allow for the storage of immune memory, the direct elimination of invading threats, or signaling to other immune cells to direct the immune response. Like an orchestra composed of highly skilled musicians using painstakingly crafted instruments to perform masterpieces written by composers of world renown – the capabilities of the immune system are allowed by its intricacy, efficiency, and beauty.

- Janeway, Charles A., Jr., et al. “Principles of Innate and Adaptive Immunity.” Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease, 5th ed., Garland Science, 2001, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK27090. ↩︎

- Ngoenkam, Jantima, Wolfgang W. Schamel, and Somchai Pongcharoen. “Selected Signalling Proteins Recruited to the T-Cell Receptor–CD3 Complex.” Immunology, vol. 153, 2018, pp. 42–50, https://doi.org/10.1111/imm.12809. ↩︎

- Chopp, Lauren, et al. “From Thymus to Tissues and Tumors: A Review of T-Cell Biology.” Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, vol. 151, no. 1, Jan. 2023, pp. 81–97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2022.10.011. ↩︎

- Adu-Berchie, K., F. O. Obuseh, and David J. Mooney. “T Cell Development and Function.” Rejuvenation Research, vol. 26, no. 4, Aug. 2023, pp. 126–138, https://doi.org/10.1089/rej.2023.0015. ↩︎

© 2025 WithinOncology. All rights reserved.

This article, including all text, tables, and figures, is the intellectual property of WithinOncology and its contributors. Unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or use of any content without explicit written permission is strictly prohibited. For inquiries, please contact us via the contact form.

Leave a comment