For most localized solid tumors, including breast cancer, the initial treatment typically involves surgical removal of the tumor. This is often followed by localized radiation therapy, which targets remaining cancer cells in the affected area and helps ensure clean surgical margins – the border between healthy tissue and tumor tissue that was removed. In many early-stage breast cancer cases, surgery combined with radiation may be sufficient. However, certain subtypes, such as triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) or those characterized by specific features like Human Epidermal growth factor Receptor 2 (HER2) overexpression, are known to be more aggressive and often require additional, targeted therapies, even when diagnosed early1.

Targeted therapies in HER2-positive breast cancer

HER2 receptor overexpression occurs in approximately 15–25% of breast cancers and is associated with a poor prognosis2. However, having a clearly identifiable molecular target on cancer cells provides an important advantage for drug development. If cancer cells display a feature that distinguishes them from healthy cells, that feature may be used to guide treatments. Indeed, recent advances in HER2-targeted therapies, particularly antibodies and antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), have significantly improved outcomes for this patient population.

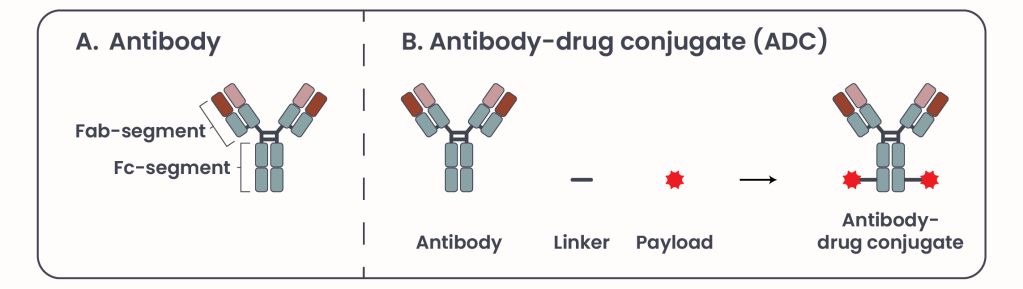

Figure 1. Antibody and Antibody-drug conjugate structure.

Antibodies are composed of two key regions (Figure 1A): the Fragment antigen-binding (Fab) and the Fragment crystallizable (Fc) segment. The Fab segment -as the name suggests- binds specifically to antigens, such as HER2, on the tumor cell surface, bringing the antibody near to the tumor cell, while the Fc segment engages the immune system to elicit a cytotoxic response. HER2-targeted antibodies induce immune-mediated cell death, and block HER2 signaling pathways essential for tumor growth .

Currently, two FDA-approved HER2-targeted antibodies are in clinical use: trastuzumab and pertuzumab, which can be used in combination. Unlike traditional chemotherapy drugs, which affect both cancerous and healthy cells, antibodies are highly target-specific. They recognize and bind exclusively to their intended antigen, much like a key fitting into a specific lock, thereby minimizing off-target toxicity. However, infusion reactions like fever, rash, and chest pain that can occure during or after an intravenous (IV) infusion are among the most common side effects associated with antibody therapy, particularly during the initial infusions.

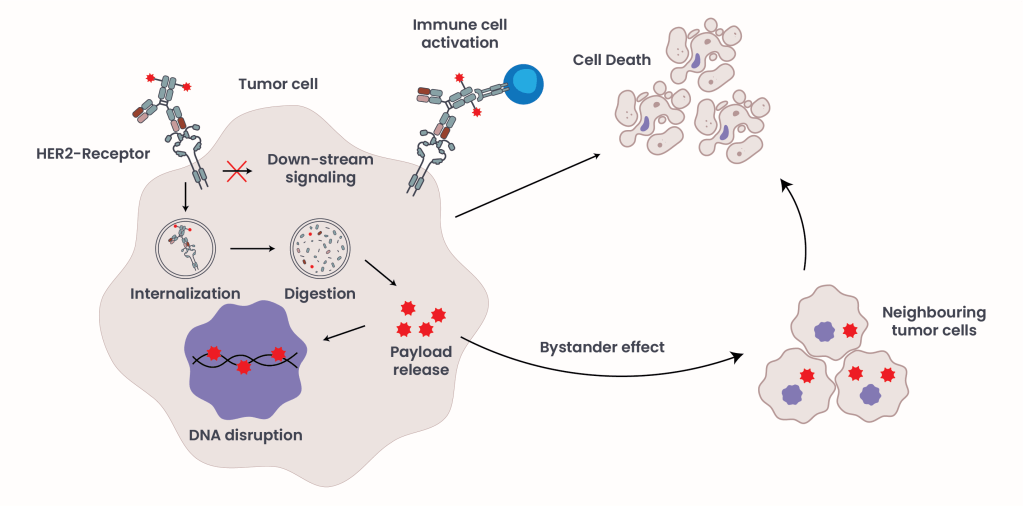

ADCs enhance the therapeutic potential of antibodies by combining them with a toxic payload, a known substance known to be toxic for the cell like a chemotherapeutic agent, via a linker (Figure 1B)3, 4. Their mechanism of action (MOA) involves two primary components: the mechanism described above of antigen recognition and immune system activation comprises the first component, and the second component consists of internalization and release of the payload into the cell, leading to cell death (Figure 2). ADCs offer a unique advantage by uniting the precision of targeted therapy with the potency of chemotherapy, minimizing off-target toxicity. Common side effects include nausea, fatigue, anemia, and pneumonitis.

In addition to their direct anti-tumor effects, ADCs of the second generation can also exert an indirect cytotoxic effect known as the bystander effect. After the ADC is internalized and the cytotoxic payload is released within a HER2-positive tumor cell, the payload may diffuse into and eliminate neighboring cancer cells, enhancing overall tumor clearance3, 4. This is particularly beneficial in heterogeneous tumors where not all cells or only a few express HER2 at low levels. In this context, ADCs can bind to HER2-expressing tumor cells and induce direct cell death, while neighboring HER2-negative tumor cells are eliminated through the bystander effect, without requiring HER2 expression.

Figure 2. ADC Mechanism of Action.

Currently, two ADCs are FDA-approved for the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer: trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) and trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) (Table 1). Although this article focuses on HER2-positive disease, it is important to note that two additional ADCs, datopotamab deruxtecan (Dato-DXd) and sacituzumab govitecan (SG), are approved for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), targeting TROP-2, a receptor expressed in over 90% of breast cancers (Table 1).

| Drug Name | Function |

|---|---|

| Taxane | Chemotherapy drug |

| Capecitabine | Chemotherapy drug |

| Trastuzumab | anti-HER2 antibody |

| Pertuzumab | anti-HER2 antibody |

| Trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) | First generation ADC: anti-HER2 antibody linked to a chemotherapy drug |

| Trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) | Second generation ADC: anti-HER2 antibody linked to a chemotherapy drug |

| Datopotamab deruxtecan (Dato-DXd) | ADC: anti-TROP2 antibody linked to a chemotherapy drug |

| Sacituzumab govitecan (SG) | ADC: anti-TROP2 antibody linked to a chemotherapy drug |

Table 1. First- and second-line breast cancer treatment regiments and their targets.

The current first-line treatment for HER2-positive breast cancer was established in 20125 and includes trastuzumab and pertuzumab combined with the chemotherapy agent taxane. However, ADCs are beginning to challenge the dominance of antibody-only regimens. A recent pivotal phase 3 clinical trial (DESTINY-Breast09, NCT04784715)6 demonstrated that combining T-DXd with pertuzumab improved progression-free survival by 13.8 months in patients with advanced or metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer, compared to standard first-line therapy. Ongoing trials will determine whether T-DXd monotherapy may ultimately replace current first-line regimens and further enhance survival outcomes.

ADC resistance

ADCs represent a promising class of therapeutics, where any potential antibody can be combined with any potential payload like a plug-and-play system, they have potential applications not only in breast cancer but also other cancer types.

Figure 3. ADC as combination therapy.

ADCs represent a promising class of therapeutics, functioning like a plug-and-play system where virtually any antibody can be paired with a range of cytotoxic payloads. While they have shown significant success in breast cancer, their potential applications extend to a variety of other cancer types as well. However, currently the development of resistance remains a significant clinical challenge7. Loss of target antigen expression, defects in internalization, and limited cytotoxic potency of the payload can all contribute to reduced efficacy. To overcome these barriers, current research is exploring strategies that combine multiple unique ADCs, or combining them with other treatments such as checkpoint inhibitors, kinase inhibitors, or conventional chemotherapies. These combinations aim to enhance anti-tumor activity while minimizing overlapping toxicities (Figure 3B).

Conclusion

The emergence of resistance remains a critical challenge in ADC therapy, potentially limiting long-term effectiveness. However, ADCs have established a pivotal role in the treatment of both HER2-positive and HER2-low breast cancer, demonstrating superior efficacy compared to traditional first-line therapies. This has translated into significant improvements in progression-free and overall survival for many patients.

- Nolan, Emma, et al. Deciphering Breast Cancer: From Biology to the Clinic. Cell, Volume 186, Article 8 (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.01.040. ↩︎

- Nolan E, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE. Deciphering breast cancer: from biology to the clinic. Cell. 2023 Apr 13;186(8):1708-1728. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.01.040. Epub 2023 Mar 16. PMID: 36931265. ↩︎

- Sun L, Jia X, Wang K, Li M. Unveiling the future of breast cancer therapy: Cutting-edge antibody-drug conjugate strategies and clinical outcomes. Breast. 2024 Dec;78:103830. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2024.103830. Epub 2024 Oct 28. PMID: 39500221; PMCID: PMC11570738. ↩︎

- Li N, Yang L, Zhao Z, Du T, Liang G, Li N, Tang J. Antibody-drug conjugates in breast cancer: current evidence and future directions. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2025 Mar 20;14(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s40164-025-00632-9. PMID: 40114224; PMCID: PMC11924693. ↩︎

- Baselga J, Cortés J, Kim SB, Im SA, Hegg R, Im YH, Roman L, Pedrini JL, Pienkowski T, Knott A, Clark E, Benyunes MC, Ross G, Swain SM; CLEOPATRA Study Group. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012 Jan 12;366(2):109-19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113216. Epub 2011 Dec 7. PMID: 22149875; PMCID: PMC5705202. ↩︎

- Tolaney SM, Jiang Z, Zhang Q, Barroso-Sousa R, Park YH, Rimawi MF, Saura C, Schneeweiss A, Toi M, Chae YS, Kemal Y, Chaudhari M, Şendur MAN, Yamashita T, Casalnuovo M, Danso MA, Liu J, Shetty J, Herbolsheimer P, Loibl S; DESTINY-Breast09 Trial Investigators. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan plus Pertuzumab for HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2025 Oct 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2508668. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 41160818. ↩︎

- Saleh K, Khoury R, Khalife N, Chahine C, Ibrahim R, Tikriti Z, Le Cesne A. Mechanisms of action and resistance to anti-HER2 antibody-drug conjugates in breast cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2024 Jun 3;7:22. doi: 10.20517/cdr.2024.06. PMID: 39050884; PMCID: PMC11267152. ↩︎

© 2025 WithinOncology. All rights reserved.

This article, including all text, tables, and figures, is the intellectual property of WithinOncology and its contributors. Unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or use of any content without explicit written permission is strictly prohibited. For inquiries, please contact us via the contact form.

Leave a comment