Under the umbrella of primary prevention, there are many actions that we can take to reduce the risk of developing cancer during our lifetime. Some are well known – like avoiding tobacco products – but others may be less recognized, like breastfeeding.

It’s now widely acknowledged that breastfeeding, when possible, offers numerous benefits to the baby: it strengthens the immune system1, reduces the risk of obesity2 (and its associated diseases), lowers chronic inflammation3 and decreases the incidence of other diseases like asthma and type 2 diabetes2. However, the benefits for mothers are often overlooked. In addition to reducing maternal risk of cardiovascular disease4 and diabetes5, it also appears to lower the risk of breast6,7 and ovarian cancer8. Reflecting this modern understanding, breastfeeding is included in the 14 recommendations of the European Code Against Cancer9 as a primary prevention strategy.

| Note: Nursing is not always easy or possible. The following information is intended to help parents make informed decisions in cases where breastfeeding is an option. |

Breastfeeding vs breast cancer

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in women worldwide and, despite major advancements in treatment, continues to be one of the leading causes of cancer death10.

Already 20 years ago, a large meta-analysis of 47 studies conducted across 30 countries demonstrated a protective effect of breastfeeding against breast cancer. According to this study, the relative risk (which compares women that breastfeed vs women that don’t) of breast cancer decreases by 4.3% for every 12 months of breastfeeding (even if not continuous)7. This means that if an average American woman has about a 12.5% chance of developing breast cancer, breast feeding would reduce her risk to 12%.

The duration of breastfeeding seems to play a crucial role, showing a dose–response relationship: the longer the breastfeeding period, the greater the reduction in risk. In the following paragraphs we use the term “women” to refer to sex assigned at birth, in relation to the presence of specific organs that may be affected by cancer and to the possibility of pregnancy and breastfeeding.

The protective effect of nursing seemed quite universal and did not vary with age, menopausal status, ethnic group or age at first birth (this factor, instead, is important when we consider the effect of pregnancy on breast cancer risk – see box)6,7. Nursing is associated with lower risks of overall breast cancer incidence, decreasing the risk of both hormone receptor–positive and more aggressive subtypes like triple negative tumors11,12.

These consistent findings across populations suggest that the protective benefit of breastfeeding stems from biological factors, rather than environmental or socioeconomic determinants.

| Pregnancy and breast cancer risk: A complicated relationshipPregnancy itself can alter breast cancer risk and it seems to have a dual effect, mostly depending on the age of the mother. Pregnancy in women under age 30 reduces the risk of breast cancer, and pregnancy under age 20 nearly halves the risk relative to women who have their first child after 3013. Conversely, a first pregnancy after 30 is linked to a slightly higher risk of breast cancer compared to women without children14. In addition, any recent childbirth, regardless of age, temporarily increases breast cancer risk14,15.The reasons behind this complex relationship are not fully understood, but are thought to be linked to the hormonal changes and breast tissue modification associated with pregnancy.You can find more information on reproductive history and cancer risk here. |

How does nursing protect against breast cancer?

Florence Welch of Florence + the Machine sings “A woman is a changeling, always shifting shape.” Women’s breasts undergo remarkable transformations, particularly during pregnancy and lactation.

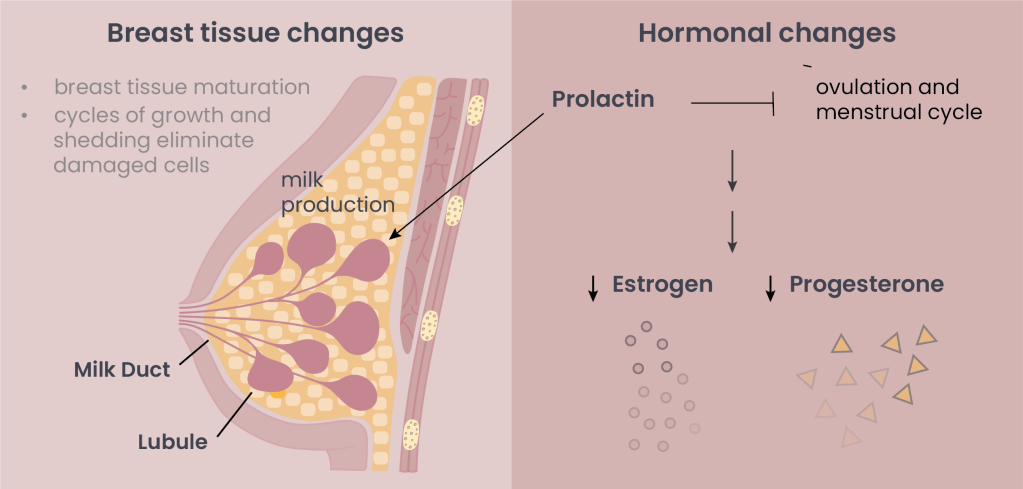

According to the National Cancer Institute, these changes may protect against breast cancer through different biological mechanisms15 (Figure 1):

- As the breast prepares to produce milk, its cells mature and differentiate, a process where unspecialized cells change structurally and functionally to take on a specialized role, like milk-production. These highly differentiated cells are thought to be less likely to become cancerous.

- High levels of prolactin, a hormone that supports lactation, can delay the return of the menstrual cycle, thereby reducing lifetime exposure to hormones like estrogen and progesterone, which can fuel certain types of breast cancers8.

- The cyclical shedding of breast tissue during and after breastfeeding may help eliminate damaged cells, reducing the chances of tumor development16.

Figure 1. Suggested protective mechanisms against breast cancer.

As an extra benefit, hormonal changes associated with breastfeeding that reduce ovulation also seem to lower the risk of ovarian cancer8. According to the “ovulatory cycle theory,” every ovulatory cycle causes repeated trauma to ovarian cells, which over time could increase the possibility of malignant transformation through mutation or inflammation.

Better support for breastfeeding

Even though breastfeeding is often described as a “natural” process, that doesn’t mean it’s easy – many “natural” things aren’t (childbirth being a perfect example!).

The European code against cancer9 and the World Health Organization (WHO)17 have called for stronger support for breastfeeding mothers – in the workplace, at home, and in public spaces.

Their recommendations include:

- Ensuring sufficient parental leave and flexible work arrangements so mothers can breastfeed for six months and continue afterwards if they wish.

- Creating breastfeeding-friendly environments in workplaces and public spaces, to protect the right of women to breastfeed whenever and wherever needed.

- Establish breastfeeding support networks. Train health-care professionals to support new mothers in breastfeeding, and make breastfeeding consultations accessible for all mothers.

- Implement regular public health campaigns to raise awareness about the benefits of breastfeeding for both mothers and babies.

WHO guidelines also recommend restricting formula milk advertising, ensuring that it is available when needed but not promoted as a substitute for breastfeeding.

A personal and informed choice

Breastfeeding (and having children at all) is a highly individual decision, influenced by many factors besides breast cancer risk. Whether or not breastfeeding is possible, there are many other lifestyle choices that can help reduce breast cancer risk: maintaining a healthy weight, exercising regularly, eating nutritious food, avoiding alcohol and tobacco products18. Also, hormone replacement therapy to treat menopause symptoms can increase breast cancer risk, so the American Cancer Society recommends talking to your health care provider about non-hormonal options to treat menopausal symptoms18.

While not every mother can or will breastfeed, ensuring that every woman has the information, support, and freedom to make her own choice is a key step toward better health for all.

This article is meant to be purely educational, to raise awareness about the role of breastfeeding in primary prevention against cancer.You can find more information about other lifestyle-related breast cancer risk factors here.

- Camacho-Morales A, Caba M, García-Juárez M, Caba-Flores MD, Viveros-Contreras R, Martínez-Valenzuela C. Breastfeeding Contributes to Physiological Immune Programming in the Newborn. Front Pediatr. 2021 Oct 21;9:744104. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.744104. PMID: 34746058; PMCID: PMC8567139. ↩︎

- Horta BL, Loret de Mola C, Victora CG. Long-term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:30-37. ↩︎

- McDade Thomas W., Metzger Molly W., Chyu Laura, Duncan Greg J., Garfield Craig and Adam Emma K. 2014Long-term effects of birth weight and breastfeeding duration on inflammation in early adulthood. Proc. R. Soc. B. 28120133116

http://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.3116. ↩︎ - Nguyen B, Gale J, Nassar N, et al. Breastfeeding and cardiovascular disease hospitalization and mortality in parous women: evidence from a large Australian cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011056. ↩︎

- Jager S, Jacobs S, Kroger J, et al. Breast-feeding and maternal risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2014;57:1355-1365. ↩︎

- Stordal B. Breastfeeding reduces the risk of breast cancer: A call for action in high-income countries with low rates of breastfeeding. Cancer Med. 2023 Feb;12(4):4616-4625. doi: 10.1002/cam4.5288. Epub 2022 Sep 26. PMID: 36164270; PMCID: PMC9972148. ↩︎

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and breastfeeding: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 50302 women with breast cancer and 96973 women without the disease. Lancet Lond Engl. 2002;360:187-195. ↩︎

- Cramer DW. Incessant ovulation: a review of its importance in predicting cancer risk. Front Oncol. 2023 Oct 6;13:1240309. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1240309. PMID: 37869082; PMCID: PMC10588628. ↩︎

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. (n.a.) European Code Against Cancer, 5th Edition. Retrieved 25 October, 2025 from https://cancer-code-europe.iarc.who.int/. ↩︎

- Wilkinson L, Gathani T. Understanding breast cancer as a global health concern. Br J Radiol. 2022 Feb 1;95(1130):20211033. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20211033. Epub 2021 Dec 14. PMID: 34905391; PMCID: PMC8822551. ↩︎

- Ma, H., Bernstein, L., Pike, M.C. et al. Reproductive factors and breast cancer risk according to joint estrogen and progesterone receptor status: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Breast Cancer Res. 8, R43 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr1525. ↩︎

- Islami F, Liu Y, Jemal A, et al. Breastfeeding and breast cancer risk by receptor status—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:2398-2407. ↩︎

- Bernstein L. Epidemiology of endocrine-related risk factors for breast cancer. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 2002; 7(1):3–15. ↩︎

- Kelsey JL, Gammon MD, John EM. Reproductive factors and breast cancer. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15(1):36-47. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036115. PMID: 8405211. ↩︎

- National Cancer Institute, (Reviewed: November 9, 2016) “Reproductive History and Cancer Risk”, retrieved October 26, 2025 from https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/hormones/reproductive-history-fact-sheet#r1 ↩︎

- Obeagu EI, Obeagu GU. Exploring the profound link: Breastfeeding’s impact on alleviating the burden of breast cancer – A review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024 Apr 12;103(15):e37695. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000037695. PMID: 38608095; PMCID: PMC11018178. ↩︎

- World Health Organization (4 August 2025 ), “On World Breastfeeding Week, countries urged to invest in health systems and support breastfeeding mothers”. Retrieved November 1, 2025 from https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding#tab=tab_1. ↩︎

- American Cancer Society (May 5 2025), Lifestyle-related Breast Cancer Risk Factors. Retrieved November 1, 2025 from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/risk-and-prevention/lifestyle-related-breast-cancer-risk-factors.html. ↩︎

© 2025 WithinOncology. All rights reserved.

This article, including all text, tables, and figures, is the intellectual property of WithinOncology and its contributors. Unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or use of any content without explicit written permission is strictly prohibited. For inquiries, please contact us via the contact form.

Leave a comment