by Ashley Saldana

“By the time they found the lump, I had been in recovery from my eating disorder for almost ten years. I thought I had left that part of my life behind, but then I realized it might have followed me into my cancer diagnosis. I was a single mother, juggling work, kids, and the exhaustion that never quite leaves you after you’ve spent years starving your body. Breast cancer felt like a second betrayal, coming from a body I had already spent half my life fighting.” – Marta*

According to the National Breast Cancer Foundation, about one in eight women1 in the United States will be diagnosed with breast cancer in their lifetime, making it the most common cancer among women after skin cancer. At the same time, nearly one in seven women will experience an eating disorder by their 40s or 50s2. What’s important to note, however, is that men and people of all gender identities can also develop breast cancer and eating disorders, as these conditions are not exclusive to women. Although stories like Marta’s are not unique, there currently exists a need for research and awareness on the unique challenges patients with breast cancer face that can predispose them to maladaptive coping mechanisms like disordered eating. However important for health, this crucial intersection remains overlooked, specifically when it comes to body image.

What is Body Image?

Body image includes the thoughts and feelings a person can have about their body3.

Why Can Poor Body Image Develop in People with Breast Cancer?

Breast cancer treatments can evoke changes in body composition, shape, appetite, and more. Treatment response is highly variable, and some people may experience little to no changes, while others may experience drastic changes. How can cancer therapies evoke body changes? Here are some examples:

- Surgery

Surgical intervention4 is often the first choice of treatment for breast cancer. This may include a mastectomy5, in which one or both breasts is removed as a means of eliminating breast tissue and other surrounding tissues that may contain cancer cells. Aside from removal of the entire breast, surgery may include removing part of the affected breast(s), and this may result in scarring, asymmetry between breasts, and other changes that can be distressing for patients.

- Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy6 is another common intervention against breast cancer. However, because it does not differentiate between fast-growing cancer cells and other fast-growing cells, it can cause appearance changes, such as hair loss. Sarcopenia7, or a deterioration in muscle mass and strength, can also occur, and this can induce visible changes in body composition and fat distribution8, which can also be distressing.

- Hormonal Changes: Estrogen

About 2 in 3 breast cancers9, 10 require hormones, such as estrogen11, to survive and grow. Medications may be prescribed to prevent estrogen function. Because estrogen is important for many organ systems, including skin, estrogen-targeting treatments may result in visual changes in skin elasticity and appearance.

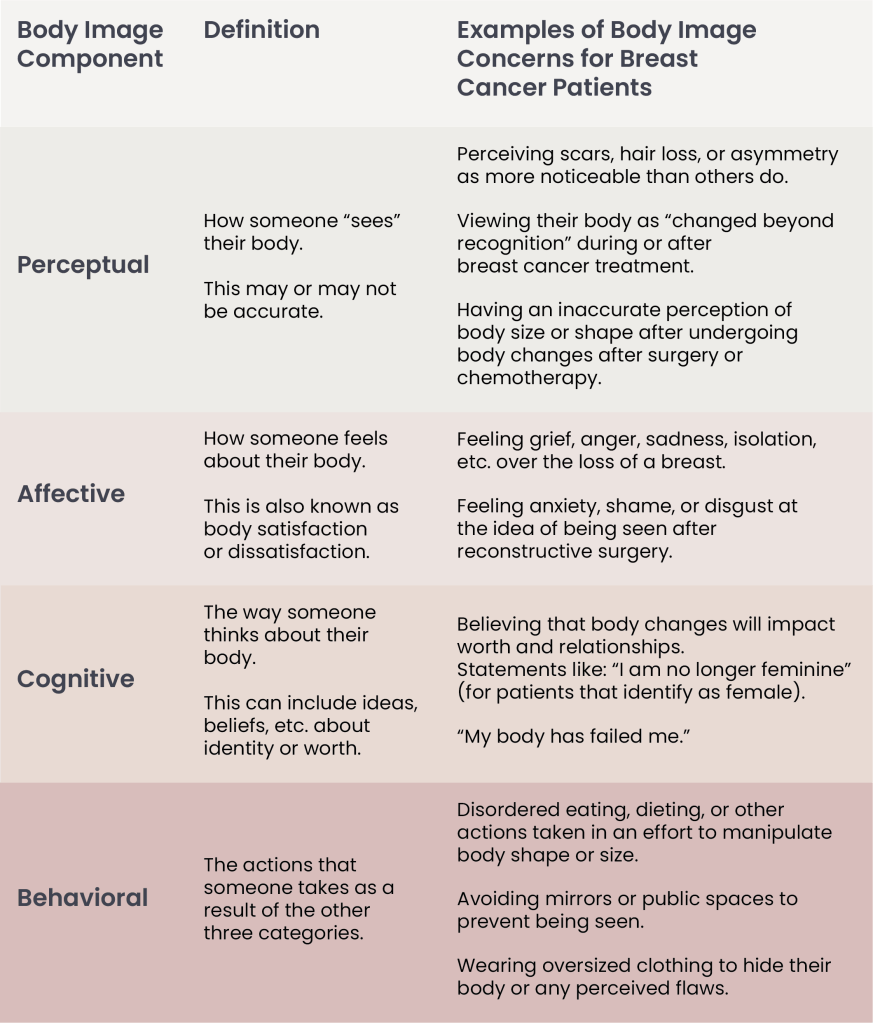

The aforementioned do not include all breast cancer treatments and all the ways they can invoke changes in appearance. Treatments are also often used in combination, and thus can evoke multiple modifications. Body changes can invoke changes in body image, and as such, special care should be taken to monitor changes in body image for patients with breast cancer. The table below shows the different components of body image3, as well as examples of what body image concerns/disturbances could look like in patients with breast cancer.

Table 1. The Different Factors of Body Image and Possible Manifestations in Breast Cancer Patients.

| Note: For patients with breast cancer, none of these changes are your fault. They are normal responses to treatment, and don’t mean that you are doing anything wrong. Talking with your care team about how these changes feel, both physically and emotionally, is an important part of healing, even after treatment occurs, and long into survivorship. |

Body Image in Patients with Breast Cancer

Body image disturbances represent critical yet insufficiently addressed12 aspects of breast cancer care. Nearly half of women diagnosed with breast cancer report significant body image concerns, and body image concerns may predispose individuals to developing disordered eating and/or eating disorders13.

Eating Disorders, a Basic Overview

Eating disorders are mental health conditions characterized by severe disturbances in an individual’s eating habits. Disordered behaviors include restriction of food intake, binge-eating, and compensatory behaviors, including self-induced vomiting, overexercising, and other weight-control behaviors. Eating disorders include Bulimia Nervosa, characterized by episodes of overeating (binge-eating) and compensatory behaviors, and Anorexia Nervosa, with subtypes that include restriction and binging-and-purging. Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (OSFED) includes disordered eating behaviors that warrant concern but do not meet criteria for one specific eating disorder. Of note, eating disorders also include Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), which is characterized by severe fear and anxiety regarding food intake and its consequences, without the weight-control and body image component. The difference between an eating disorder and disordered eating lie in the impact that the behaviors and thoughts have on one’s life.

| Note: You do not need to have a diagnosed eating disorder to be worthy of recovery and support. Struggles with food or body image are enough to warrant care. |

Body Image Care as a Safety Net

Negative body image is consistently associated with increased psychological distress as well as reduced quality of life14. What’s more, patients with breast cancer can experience changes in body composition that can warrant changes in body image. Effective breast cancer treatment, therefore, relies on not only caring for the physical body but also addressing the behaviors and emotions that come with it.

For people like Marta, a breast cancer diagnosis can re-ignite old disordered eating habits. For others, it can lead to difficult emotions and body image changes that can fuel disordered eating or an eating disorder.

Think of body image care as a safety net. For some people with breast cancer, body image struggles or disordered eating may never arise. However, having it there can be helpful and is a part of care for the whole person.

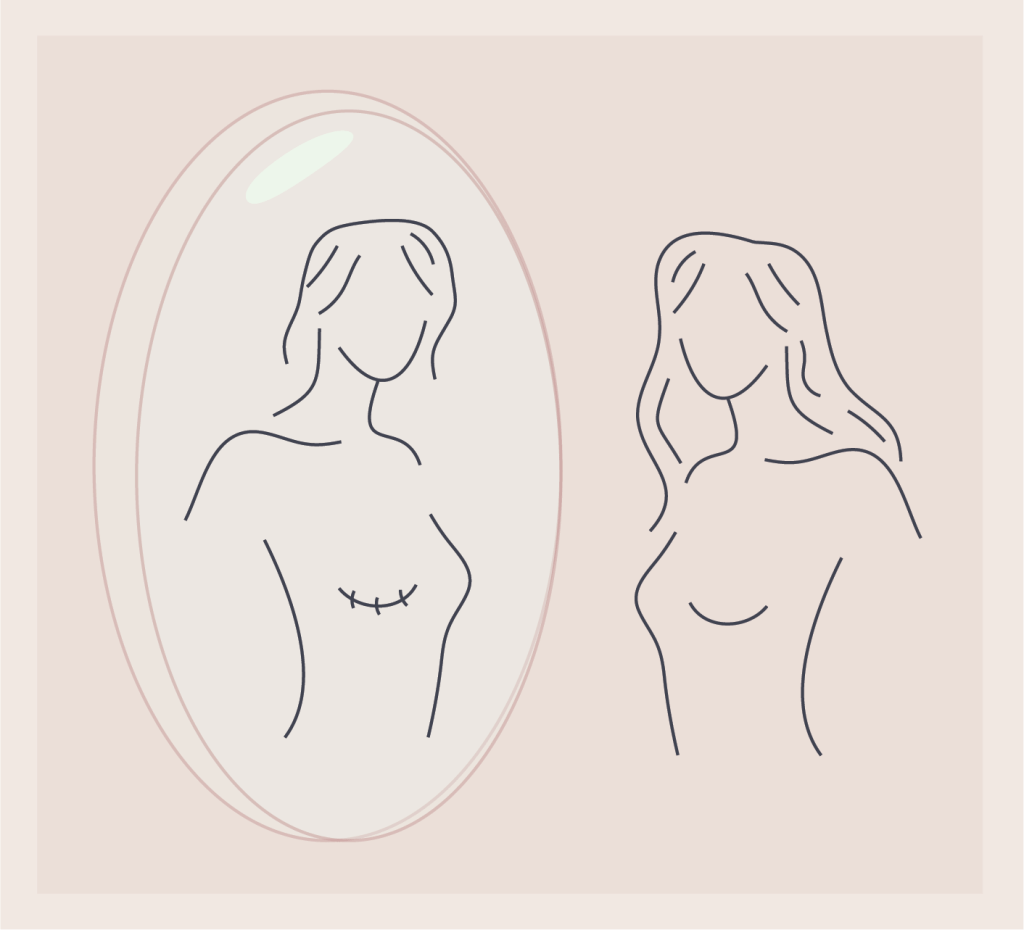

Figure 1. Perceptional Body Image.

| Note: Talking with your care team about how these changes feel, both physically and emotionally, is an important part of healing, even after treatment occurs, and long into survivorship. |

What Else Can Fuel Disordered Eating for People with Breast Cancer?

For people with breast cancer, with either a history of disordered eating or a predisposition to developing disordered eating patterns15, the process of being diagnosed and undergoing breast cancer treatment can be exceedingly and emotionally distressing. The relationship between emotions and eating disorders can be complex, and disordered eating may develop as a coping mechanism to manage the different changes that come with a diagnosis.

Moreover, for those well into survivorship, the fear of remission can cause patients to focus on what they believe may reduce their risk of remission: food16. A 2022 study17 from the Journal of Eating Behaviors found that 70% of individuals diagnosed with breast cancer vowed to change their eating habits in some way as a result of their diagnosis. Although a healthier diet can be beneficial, almost 40% of these patients met clinical criteria for Orthorexia Nervosa (ON). ON refers to a pattern of disordered eating in which an unhealthy obsession occurs over “eating [only] healthy food.” Some may wonder how eating only healthy food can be harmful. It has been shown that an unhealthy relationship with food, even if you eat only healthy food, can still lead to malnourishment and poor quality of life18.

Integrating Eating Disorder awareness into breast cancer care

With body changes being a risk factor for body image distress, individuals going through a breast cancer diagnosis deserve to have body image care incorporated into the management of their disease. This can include screenings19 for disordered eating or eating disorders (including the SCOFF Questionnaire or EAT-26), check-ins with a provider about how they feel physically or emotionally, and targeted psychotherapy or support groups for patients with breast cancer.

For providers and caretakers, taking note of changes in eating or eating concerns can be crucial20 for early detection of an eating disorder. Integrating this awareness into breast cancer care is an important step towards a more comprehensive approach that goes beyond the tumor and takes care of the patient as a whole.

Understanding what body image is and how body image disturbances can manifest into disordered eating is paramount to the treatment of the whole person, thus being essential to the treatment of breast cancer and many other cancers. In turn, this can improve treatment plans and help patients like Marta, where treatment of the eating disorder and breast cancer are necessary to improve overall quality of life. Marta’s case is one of many, and as such, more care needs to be taken to address body image in breast cancer treatment.

For providers, caretakers, and support people alike, let the diagnosis become an invitation: to design and implement care that goes beyond the tumor to care of the whole human being. Together, we can build a team that addresses people with breast cancer as a whole, and rebuild trust in one’s body and its capacity for healing, recovery, and growth.

*Note: Pseudonym used to preserve confidentiality.

- National Breast Cancer Foundation. (June 15, 2023) “Breast Cancer Facts & Statistics.” nationalbreastcancer.org. Retrieved September 24, 2025, from https://www.nationalbreastcancer.org/breast-cancer-facts/. ↩︎

- Micali, N., Martini, M.G., Thomas, J.J., et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of eating disorders amongst women in mid-life: a population-based study of diagnoses and risk factors. BMC Medicine 15, 12 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0766-4. ↩︎

- National Eating Disorders Collaboration. (2022) “Body Image.” nedc.com.au. Retrieved September 14, 2025, from https://nedc.com.au/eating-disorders/eating-disorders-explained/body-image. ↩︎

- American Cancer Society. (October 14, 2025) “Surgery for Breast Cancer | Breast Cancer Treatment.” cancer.org. Retrieved September 25, 2025, from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/treatment/surgery-for-breast-cancer.html. ↩︎

- Golara, A., Kozłowski, M., Lubikowski, J., Cymbaluk-Płoska, A. Types of breast cancer surgery and breast reconstruction. Cancers 16, 3212 (2024). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16183212. ↩︎

- Cleveland Clinic. (October 20, 2022) “Chemotherapy for Breast Cancer.” clevelandclinic.org. Retrieved September 15, 2025, from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/8340-chemotherapy-for-breast-cancer. ↩︎

- Roberto, M., Barchiesi, G., Resuli, B., et al. Sarcopenia in breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers 16, 596 (2024). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16030596. ↩︎

- Coletti, D. Chemotherapy-induced muscle wasting: an update. European Journal of Translational Myology 28, 7587 (2018). https://doi.org/10.4081/ejtm.2018.7587. ↩︎

- Al-Shami, K., Awadi, S., Khamees, A., et al. Estrogens and the risk of breast cancer: a narrative review of literature. Heliyon 9, e20224 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20224. ↩︎

- Shete, N., Calabrese, J., Tonetti, D.A. Revisiting estrogen for the treatment of endocrine-resistant breast cancer: novel therapeutic approaches. Cancers 15, 3647 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15143647. ↩︎

- Hamilton, K.J., Hewitt, S.C., Arao, Y., Korach, K.S. Estrogen hormone biology. Current Topics in Developmental Biology 125, 109–146 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.ctdb.2016.12.005. ↩︎

- Ahn, J., Suh, E.E. Body image alteration in women with breast cancer: a concept analysis using an evolutionary method. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing 5, 100214 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apjon.2023.100214. ↩︎

- Mallaram, G.K., Sharma, P., Kattula, D., Singh, S., Pavuluru, P. Body image perception, eating disorder behavior, self-esteem and quality of life: a cross-sectional study among female medical students. Journal of Eating Disorders 11, 225 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00945-2. ↩︎

- Yao H, Xiong M, Cheng Y, Zhang Q, Luo Y, Ding X and Zhang C (2024) The relationship among body image, psychological distress, and quality of life in young breast cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. Front. Psychol. 15:1411647. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1411647. ↩︎

- National Eating Disorders Association. (2024) “Eating Disorder Risk Factors.” nationaleatingdisorders.org. Retrieved September 28, 2025, from https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/risk-factors/. ↩︎

- UCLA Health. (April 23, 2025) “People with Cancer Can Develop Orthorexia, an Obsession with Healthy Foods.” uclahealth.org. Retrieved September 30, 2025, from https://www.uclahealth.org/news/article/orthorexia-when-healthy-eating-becomes-problematic. ↩︎

- Waterman, M., Lee, R.M., Carter, J.C., Garland, S.N. Orthorexia symptoms and disordered eating behaviors in young women with cancer. Eating Behaviors 47, 101672 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2022.101672. ↩︎

- Scarff, J.R. Orthorexia nervosa: an obsession with healthy eating. Federal Practitioner 6, 36–39 (2017). https://www.mdedge9-ma1.mdedge.com/fedprac. ↩︎

- Eating Disorder Hope. (December 6, 2021) “Testing and Assessments for Eating Disorders.” eatingdisorderhope.com. Retrieved September 16, 2025, from https://www.eatingdisorderhope.com/information/eating-disorder/testing-assessments. ↩︎

- Koreshe, E., Paxton, S., Miskovic-Wheatley, J. et al. Prevention and early intervention in eating disorders: findings from a rapid review. J Eat Disord 11, 38 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00758-3. ↩︎

Ashley Saldana

As an emergency medical technician (EMT) aspiring to work in the field of eating disorders, patient advocacy and health communication have always been important to me. My experience in health communication first began in San Francisco, where I worked to deliver accessible behavioral health presentations for low-income patients and community members and where I currently work to develop health curricula for younger patients and their families. As current research specialist for an eating disorder 501(c), I have had the honor of helping develop health communication initiatives that support and advocate while also holding a brave space for patients and their families. Throughout my years working with various patient populations, I have had the privilege of witnessing firsthand how transformative health communication can be. I believe that empowering patients and their families to know more about what impacts their health can help them feel seen, understood, and actively involved in their own care. Although the connection may not seem intuitive at first, I have worked and interacted with various individuals whose personal journeys have been marked by both cancer and disordered eating. I believe that health communication can help bridge the gap between scientific knowledge and lived experience, in turn leading to deliver more compassionate and informed healthcare.

Values:

Authenticity/Transparency | Advocacy | Compassion | Inclusivity | Courage | Curiosity

© 2025 WithinOncology. All rights reserved.

This article, including all text, tables, and figures, is the intellectual property of WithinOncology and its contributors. Unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or use of any content without explicit written permission is strictly prohibited. For inquiries, please contact us via the contact form.

Leave a comment