If there ever was a poster child of cancer types, breast cancer would certainly be a contender – and for good reason. Among cancer in women, it is the most common across the world, and the first or second most deadly, depending on the country1. Spanning across decades, breast cancer has been the focus of numerous impact campaigns leading to successful fundraising initiatives and increased research spending. These efforts have increased our understanding of breast cancer as a complex, multifaceted disease, allowing for better detection and treatment strategies, leading to improved health outcomes: breast cancer mortality dropped by 58% from 1975 to 20191.

In many ways the discovery of biology is like discovering the world – the more we understand, the clearer the whole picture becomes, while also opening new doors previously unseen. Imagine an explorer coming upon a new land for the first time – what would they learn first? Where it is (as long as they don’t think they are close to India), and how it looks from afar. Similarly, the first clinical feature an oncologist observes in breast cancer is the histological subtype, or where and how it appears.

Land, Ho! The first observations of a tumor

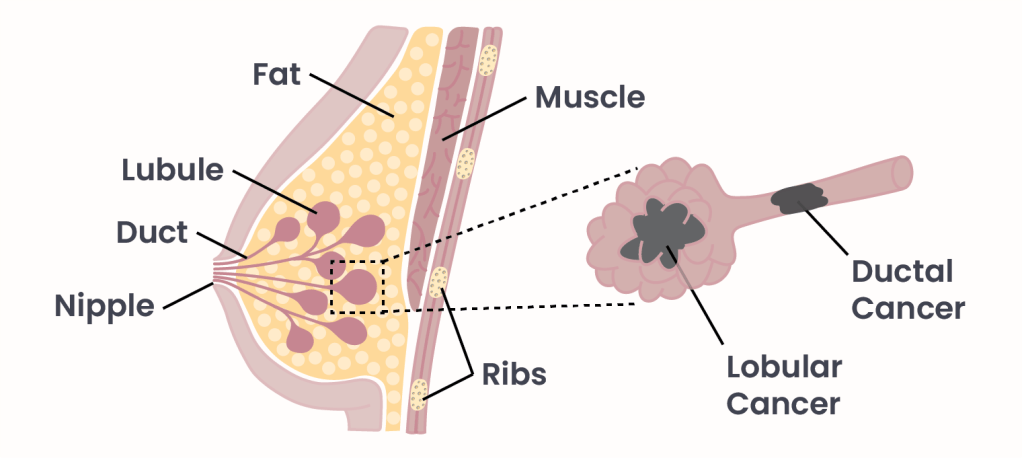

Figure 1. Types of Breast Cancer.

Breast cancer mainly arises from two parts of the breast: lobules, round glands that produce milk, and milk ducts, tubes that carry milk to the nipple (Figure 1). Although rare, cancer can also arise from other breast tissues such as stroma (tissue that surrounds the ducts and lobules), or blood and lymph vessels2, as well as lobules and ducts in men3. Cancers that are caught while still confined to their tissues of origin are called in situ (“in place” in latin) carcinomas: ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). Tumors that have progressed and spread to the stroma, or surrounding tissue, are called invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) or invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC). Cancer evolves by gaining new genetic and epigenetic mutations, allowing it to progress from in situ to invasive, and eventually to metastatic, spreading to other sites in the body. Breast cancers can be further divided based on which of its genes have been mutated or are misregulated, giving information on how aggressive the cancer will be, and which treatments will be effective. To an explorer, these would be the finer details of a newly discovered land, appreciable only after setting foot on the foreign beaches – where fresh water can be found, the local fauna that reside there, what wildlife threats must be looked out for.

More than meets the eye

Anyone that has been close to an individual fighting breast cancer has likely heard “positive-this-or-that” or “negative for xyz” regarding the diagnosis. Breast cancers are defined by their “receptor status,” indicating mutations that result in overactivation of a receptor. Receptors are proteins that sit on the cell membrane or reside inside of the cell and allow for communication with other cells by way of a signaling molecule. When a signaling molecule finds its way to and activates a receptor, it triggers a cellular response. Cellular responses can vary, but some that are critical for cancer to regulate cell growth, survival, and movement (metastasis) – critical hallmarks of cancer.

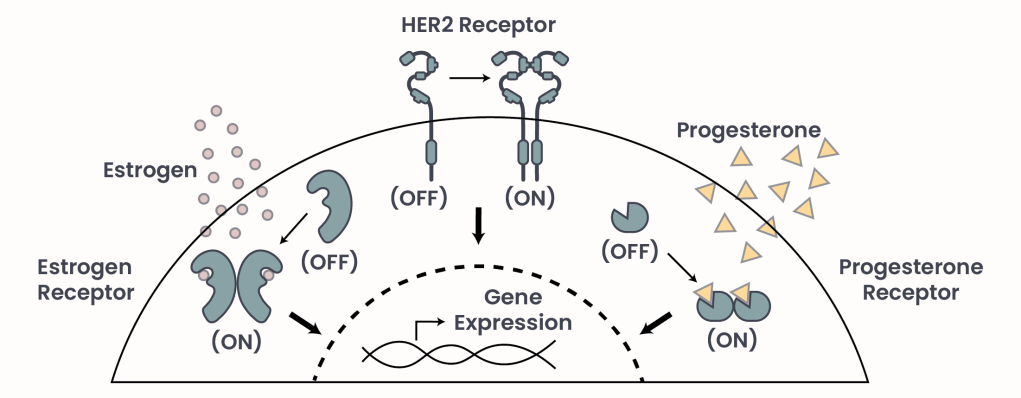

Figure 2. The drivers of breast cancer.

When the mutation or misregulation of a gene is so critical to persistence of the cancer, it is known as a “driver” of the cancer. The most common drivers of breast cancer are Estrogen Receptor (ER), Progesterone Receptor (PR), and Human Epidermal growth factor Receptor 2 (HER2) (Figure 2). While ER and PR respond to the hormones estrogen and progesterone, respectively, HER2 becomes activated upon interacting with another HER2 receptor. If a cancer is positive for one or multiple receptors, it means that1 those receptors are over-activated due to mutations or misregulation2, the cancer depends on them, and3 their targeting may be clinically beneficial. Indeed, targeting the culprit receptor, or preventing its activation, is a potent and commonly employed treatment strategy. If these three main receptors are not driving the tumor, it is called a triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) that will not respond to any receptor-targeted therapy, which is typically more aggressive with a worse prognosis4. Receptor status contributes greatly to treatment planning, but is not the end of classifications. Just as explorers gather all the information available before making detailed plans to inhabit newly discovered lands, oncologists harness decades of research to further subdivide cancer types and develop the most accurate plan possible.

Russian dolls of classification

Receptors, however important, represent just a few out of tens of thousands of genes. Genes can be mutated, or expressed too often. By looking at gene mutations and their regulation, measured in terms of how often the gene is used, or its “expression,” we can discover cancer’s true identity and, most importantly, its Achilles tendon. Correlating the expression of thousands of genes with various observations related to breast cancer (stage of diagnosis, aggressiveness, response to treatment, metastatic potential, etc…) allows us to further categorize cancers. To date, numerous subtypes have been identified4. The list continues to expand as research progresses and identifies more defining features of breast cancer. These subtypes are used to guide treatment strategies, and predict responses. The use of genetic analysis also extends to predicting risk for cancer. In particular, BRCA1 and BRCA2 are genes that, when mutated, promote the risk of breast and other cancers. They have become infamous as mutated versions can be inherited, drastically increasing chances of many cancers – in particular, causing breast cancer in more than one in two mutation-bearing individuals by age 705.

Treating is good, catching early is better, but preventing is best

The journey of investigating breast cancer continues, but it’s important to recognize the massive amount of discovery along the way that has saved or improved the lives of countless people. Leaps and bounds made in treating breast cancer have been mirrored by improvements in prevention and early detection. We’ve learned that breast cancer chances can be minimized by reducing alcohol and smoking, staying at a healthy weight, and being active6. Early detection is a multipronged effort, taking into account familial occurrence of cancers, genetic testing, and regular screening. Screening in particular has had a significant impact on reducing breast cancer mortality1. Hopefully the mortality rate of breast cancer continues to drop – but it won’t do it on its own. It is our job not only to support science and thus improve health outcomes, but also to mitigate cancer risk by looking after our own individual health diligently.

- Caswell-Jin, Jennifer L., et al. “Analysis of Breast Cancer Mortality in the US—1975 to 2019.” JAMA, vol. 331, no. 3, 16 Jan. 2024, pp. 233–241, jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2813878, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.25881. ↩︎

- American Cancer Society. (Revised 19 November, 2021). Types of Breast Cancer. cancer.org. Retrieved October 5, 2025 from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/about/types-of-breast-cancer.html. ↩︎

- American Cancer Society. (Revised 16 January, 2025) . Key Statistics for Breast Cancer in Men. cancer.org. Retrieved October 5, 2025 from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer-in-men/about/key-statistics.html. ↩︎

- Nolan, Emma, et al. Deciphering Breast Cancer: From Biology to the Clinic. Cell, Volume 186, Article 8 (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.01.040. ↩︎

- Petrucelli, Nancie, et al. BRCA1- and BRCA2-Associated Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer. GeneReviews, University of Washington. 21 Sept. 2023.m Retrieved October 5, 2025 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1247/. ↩︎

- Mayo Clinic. (Revised 1 December, 2023) “Breast Cancer: How to Reduce Your Risk.” mayoclinic.com. Retrieved October 5, 2025, from www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/womens-health/in-depth/breast-cancer-prevention/art-20044676. ↩︎

© 2025 WithinOncology. All rights reserved.

This article, including all text, tables, and figures, is the intellectual property of WithinOncology and its contributors. Unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or use of any content without explicit written permission is strictly prohibited. For inquiries, please contact us via the contact form.

Leave a comment