Vaccines are already widely employed to fight common oncogenic viruses such as human papilloma virus and hepatitis B, but may also be used to fight cancer itself. Cancer cells often change enough to no longer be recognized as healthy cells of our own body, but as invaders to be dealt with by the immune system: our immune system is constantly active and clearing cancerous cells before they become tumors. However, natural responses may not be sufficient, and cancers can dampen immune responses through unique mutations.

How Cancer Vaccines Work

Vaccine-based therapies represent a potent, yet still developing arm of the immunotherapy approach. In a nutshell, vaccines potentiate the natural ability of our immune system to recognize threats, and then develop a strong response against them. A known threat is presented in a harmless way during vaccination, so as to “train” our immune system to respond to the threat in future encounters when exposure may not be harmless. The idea behind cancer vaccines is to provide and target tumor-associated antigens (TAA) that are present in high quantities on cancer cells, but either not present, or present in very low quantities on normal cells. Dendritic cells, a type of antigen presenting cell (APC), will expose these antigens to T-cells in order to facilitate immune responses, helping to attack cancer cells. Cancer vaccines help the immune system learn to recognize and react to these antigens and destroy cancer cells that contain them1.

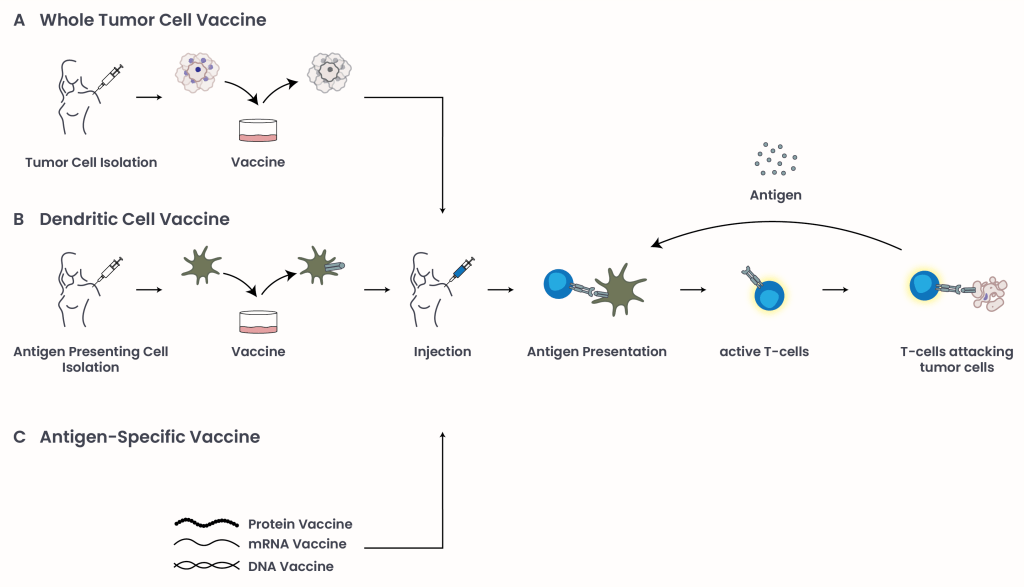

There are three main types of cancer vaccines (Figure 1):

- Whole Tumor Cell Vaccines (Figure 1A): Doctors can remove tumor cells from a patient, treat them so they can’t grow but are easier for the immune system to recognize, and inject them back into the body. This exposes the immune system to all possible cancer markers, potentially triggering a powerful, personalized immune response.

- Dendritic Cell Vaccines (Figure 1B): Dendritic cells are a type of immune cell that engulf foreign threats, and expose their antigens to types of white blood cells called T-cells in order to facilitate immune responses. Cancer patient dendritic cells can be removed, then treated with TAAs in a lab setting. The dendritic cells take up these antigens, and then expose them on their cell surface. Once placed back in the cancer patient, stimulated dendritic cells present their new TAA to T-cells to stimulate a strong response. The first FDA-approved vaccine of this kind is Sipuleucel-T (PROVENGE, by Dendreon Pharmaceuticals) for advanced prostate cancer, and is described below.

- Antigen-Specific Vaccines (Figure 1C): Advances in research have identified tumor-specific antigens (TSA), also known as neoantigens. Unlike TAAs, these antigens are highly specific to tumor cells since they arise from mutations that do not exist in normal cells, e.g. mutant KRAS. Antigen-specific vaccines involve the delivery of these antigens using DNA, mRNA, or protein fragments. This approach may benefit a wide range of patients, since these TSA are shared across tumor types.

Figure 1: Types of cancer vaccines: Tumor antigens can be presented to the immune system to stimulate an immune response and target cancer cells through three main approaches: (A) whole tumor cell vaccines, which expose the immune system to a broad array of tumor-associated markers; (B) dendritic cell vaccines, which are engineered in the laboratory with TAAs to prime T-cell responses; and (C) antigen-specific vaccines, which deliver personalized tumor antigens using DNA, mRNA, or protein fragments. Dying cancer cells release new antigens, re-stimulating an immune response.

Example: Personalized Immunotherapy for Advanced Prostate Cancer

Sipuleucel-T (PROVENGE)2 was approved by the FDA in 2010 for men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), a stage of prostate cancer that has spread to distant organs and no longer responds to standard hormone therapy.

Here’s how it works:

- Doctors collect antigen presenting cells (APCs) (including dendritic cells) from the patient’s blood.

- In a lab, these cells are “trained” through exposure to prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP), a protein found on prostate cancer cells.

- The “trained” APCs are infused back into the patient, helping the body’s immune system recognize and attack prostate cancer cells positive for PAP.

In a phase 3 clinical trial, this approach improved median survival by about four months, from 21.7 months with placebo to 25.8 months with the vaccine (IMPACT, NCT00065442)3.

New Cancer Vaccines on the Horizon

Recent development in mRNA vaccines due to COVID-19 or combinatorial approaches with immune checkpoint inhibitors to maintain continued T-cell activation has progressed into an era of promise. Here are some cancer vaccines currently in clinical trials:

- mRNA-4157/V940 (by Moderna and Merck):

A personalized vaccine designed to help the immune system target unique mutations (neoantigens) in each patient’s tumor. The vaccine uses messenger RNA (mRNA) to deliver instructions to the body’s immune cells to produce these specific neoantigens. Phase IIb-IV clinical trials are underway for resected high-risk melanoma (INTerpath-001, NCT05933577)4 and non-small cell lung cancer (INTerpath-002, NCT06077760)5 evaluating mRNA-4157/V940 in combination with immunotherapy. - Adagloxad Simolenin (by OBI Pharma):

Targets a carbohydrate called Globo H, a marker found on some breast cancer cells. Currently in a phase 3 trial for Globo H-positive triple-negative breast cancer (GLORIA, NCT03562637)6. - IO102-IO103 (by IO Biotech):

Combines two vaccines to activate T-cells against IDO1 and PD-L1-positive cancer cells. Being tested in a phase 3 trial in advanced melanoma patients alongside immunotherapy (NCT05155254)7. - OSE2101 (by OSE Immunotherapeutics):

A multi-target vaccine targeting antigens frequently found in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), including CEA, HER-2, MAGE-2, MAGE-3, and P53. Being studied in a phase 3 clinical trial for NSCLC patients with a secondary resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) (ARTEMIA, NCT06472245)8.

Note: These vaccines are still being studied. No final results are available yet.

Oncolytic Virus Therapy: Using Viruses to Fight Cancer

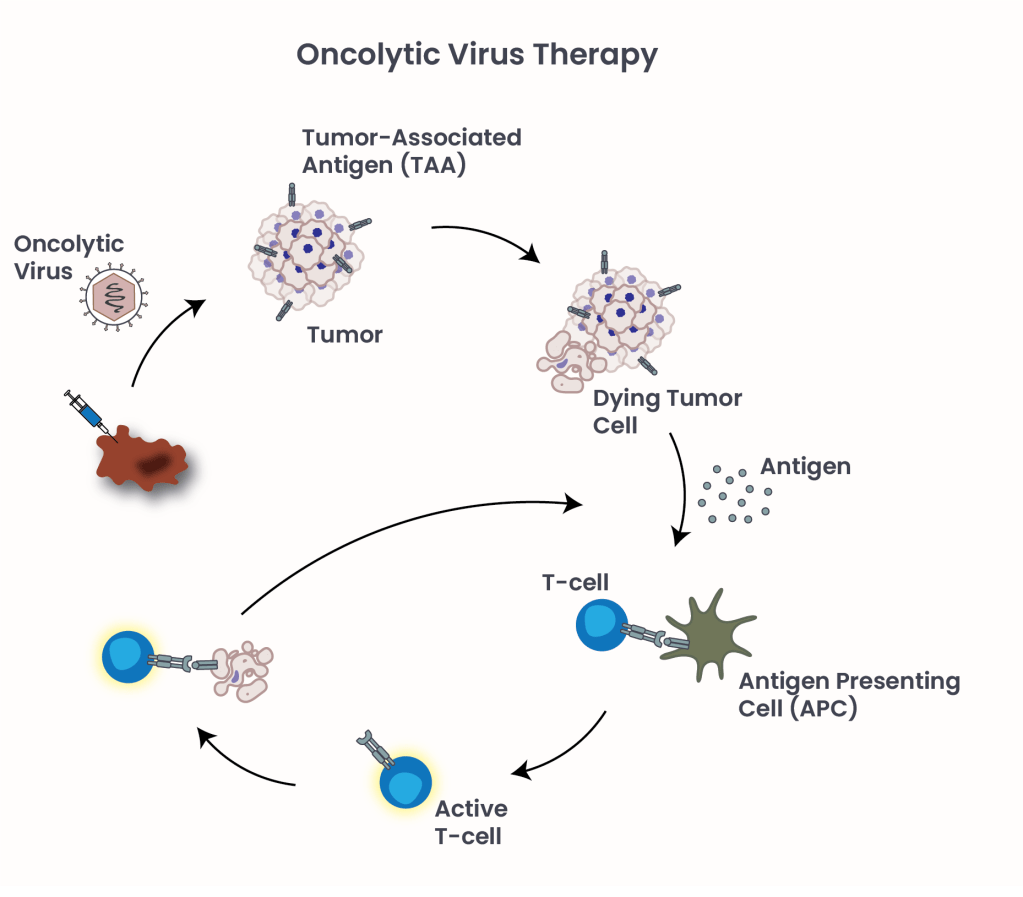

Figure 2: Oncolytic Virus Therapy. Oncolytic virus causes cancer cells to burst and die, triggering an immune response against cancer cells throughout the body.

Oncolytic viruses (OVs) represent a novel class of cancer immunotherapy agents, where viruses are modified to infect and destroy cancer cells while sparing healthy ones9. OVs are injected directly into a tumor, where the virus makes more and more copies of itself and causes cancer cells to burst and die. The dying cells release new viruses and other substances, such as tumor antigens, alerting the immune system to the presence of cancer cells and triggering an immune response against cancer cells throughout the body (Figure 2).

FDA-approved in 2015, Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) is the first oncolytic virus therapy specifically used for unresectable, metastatic melanoma. It uses a genetically modified herpes simplex virus to target and destroy cancer cells.

The Future of Cancer Vaccines

Cancer vaccination therapy is a promising, yet still new technology. With plenty of room to cover, advances in our understanding of how cancer and our immune system interact, and where in that process we can intervene, will undoubtedly lead to new breakthroughs, and better treatments.

- National Cancer Institute.(updated 24 Sept. 2019), Immunotherapy for Cancer. cancer.gov. Retrieved June 28, 2025, from https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types/immunotherapy. ↩︎

- Dendreon Pharmaceuticals. (n.d.), Immunotherapy For Advanced Prostate Cancer. https://www.dendreon.com/.Retrieved June 28, 2025, from https://provenge.com/. ↩︎

- National Library of Medicine. (updated 6 Sept. 2010), clinicaltrial.gov. Retrieved June 28, 2025, from https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00065442. ↩︎

- National Library of Medicine. (updated 13 May 2025), clinicaltrial.gov. Retrieved June 28, 2025, from https://cts.businesswire.com/ct/CT?id=smartlink&url=https%3A%2F%2Fclassic.clinicaltrials.gov%2Fct2%2Fshow%2FNCT05933577&esheet=54142489&newsitemid=20241028767283&lan=en-US&anchor=NCT05933577&index=1&md5=65c5d3a89b1a696153164316c4fdf02d. ↩︎

- National Library of Medicine. (updated 22 June 2025), clinicaltrial.gov. Retrieved June 28, 2025, from https://cts.businesswire.com/ct/CT?id=smartlink&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.clinicaltrials.gov%2Fstudy%2FNCT06077760%3Fintr%3DmRNA-4157%26rank%3D3&esheet=54142489&newsitemid=20241028767283&lan=en-US&anchor=NCT06077760&index=2&md5=3b6c8890f611a28c3b5b7a81720840aa. ↩︎

- National Library of Medicine. (updated 9 May 2025), clinicaltrial.gov. Retrieved June 28, 2025, from https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03562637?term=NCT03562637&rank=1. ↩︎

- National Library of Medicine. (updated 9 Jan. 2024), clinicaltrial.gov. Retrieved June 28, 2025, from https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05155254?term=NCT05155254&rank=1. ↩︎

- National Library of Medicine. (updated 20 May 2025), clinicaltrial.gov. Retrieved June 28, 2025, from https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06472245?intr=OSE2101&rank=4. ↩︎

- National Cancer Institute.(updated 9 Feb. 2018), Oncolytic Virus Therapy: Using Tumor-Targeting Viruses to Treat Cancer. cancer.gov. Retrieved June 28, 2025, from https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2018/oncolytic-viruses-to-treat-cancer. ↩︎

© 2025 WithinOncology. All rights reserved.

This article, including all text, tables, and figures, is the intellectual property of WithinOncology and its contributors. Unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or use of any content without explicit written permission is strictly prohibited. For inquiries, please contact us via the contact form.

Leave a comment