“Few people associate infections with cancer, but nearly one-fifth of all cancers in the world are caused by infectious agents, including viruses and bacteria” [European Code Against Cancer_World Health Organization1].

Identifying the infectious agents that can lead to cancer development is the first step in primary prevention. So far, the infection of several pathogens has been associated with development of cancer including human papilloma virus (HPV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), Human T-lymphotrophic virus-1 (HTLV-1) and the bacteria Helicobacter pylori (Table 1). Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, even if it doesn’t directly cause cancer, it weakens the immune system and increases the risk of certain cancers2.

The next step for primary prevention is to develop effective vaccines against these cancer-associated pathogens. So far, science has two successful stories to tell: HPV and HBV vaccines.

Table 1. List of infectious agents associated with cancer. While vaccines for primary prevention are commercially available for HPV and HBV, no vaccines are currently on the market for the other pathogens, although significant efforts are underway to develop them2. Several antiretroviral drugs are available to block HIV replication and can reduce the risk of cancers associated with HIV infection3.

Human papillomavirus (HPV)

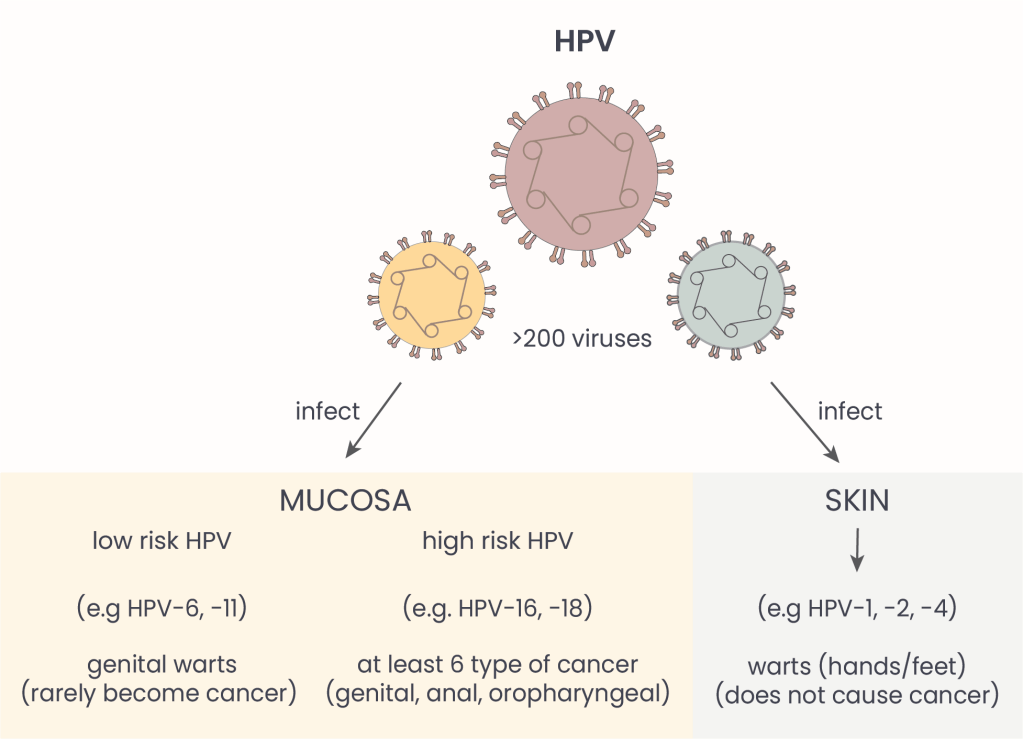

Figure 1. Human papilloma viruses. HPVs can infect the skin or mucosas, the soft lining that covers body cavities -like nose and mouth- and internal organs. Mucosal HPV types are classified as low-risk or high-risk based on their cancer-causing potential. About 12 strains are considered high risk, and this list continues to evolve as science advances4.

The association between HPV and cancer was first hypothesized in the late 1970s by the German virologist Harald zur Hausen. In the following decade, zur Hausen and his team proved that HPV infection was linked to cervical cancer – especially for high risk types 16 and 18 (see Figure 1) – and earned the Nobel prize for medicine for this discovery in 20085. Later research also linked HPV to other cancer types including genital (penis, vulva, vagina), anal and oropharyngeal cancer (the middle part of the throat, behind the mouth)6.

How does HPV cause cancer? Viruses cannot multiply on their own, so they infect other cells and force them to do the job for them. When an HPV virus infects human cells, it inserts its own genes into the DNA of the human host cell, which then produces viral proteins helping its invador to replicate. They also produce some factors that break down cellular tumor suppressors, which normally help regulate cell division and prevent uncontrolled growth. This is a “sneaky move” to extend the life-span of the host cell, so more viruses can be produced. If the immune system fails to eliminate the infection and it becomes chronic, infected cells can proliferate uncontrollably, first forming precancerous lesions (abnormal cell growth) and eventually tumors7.

HPV: one vaccine to -almost- rule them all

According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), HPV is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections in the US8. While most of the time our immune system can take care of the virus, we’ve now learned what can happen if the infection persists! Luckily, we have a powerful tool to train our immune system to identify and remove the threat more effectively: HPV vaccines.

There are several HPV vaccines currently available worldwide, as single or two/three doses depending on the brand. They can protect against different strains of HPV:

- Bivalent vaccines: Protect against two HPV types (16 and 18 – high risk).

- Quadrivalent vaccines: Protect against four HPV types (6, 11 – low risk; 16 and 18 – high risk).

- Nonavalent vaccine: Protect against nine HPV types (6, 11 – low risk and 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 – high risk).

In the United states, the first Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved HPV vaccine (Gardasil- quadrivalent by Merck) became available in 2006, and since 2017 it has been substituted by the upgraded nonavalent version (Gardasil-9 by Merck)9 which protect against about half of the known high-risk HPV types. Ideally, vaccines will continuously evolve together with the knowledge of viruses with cancer-causing potential.

When to get the HPV vaccine? As a cancer prevention method, vaccination is most effective before exposure to the virus that causes the disease. Thus, Health Institutions generally recommend HPV vaccination before sexual life begins. The American Cancer Society recommends vaccinating boys and girls between ages 9 and 129. While vaccination is still possible and safe later in life, cancer prevention benefits generally decline with age, as the likelihood of prior HPV exposure increases with age. So far, evidence shows protection does not wane over time.

Hepatitis B virus & co.

There are five main types of hepatitis viruses: A, B, C, D, and E. Apart from the shared ability to cause hepatitis (liver inflammation), these viruses differ in structure, modes of transmission and infection outcomes (Figure 2). HAV and HEV mainly cause acute (temporary and self limiting) infections, while HBV, HCV and HDV can also lead to chronic (long term) infections. HDV is an interesting member of this family: it’s considered “defective” because it cannot replicate on its own in the host cell and it requires co-infection with its sibling HBV. Although HDV is not currently included in the list of carcinogenic viruses, HBV-HDV co-infection is known to cause faster progression toward hepatocellular carcinoma (a type of liver cancer)10.

Table 2. Hepatitis viruses. These viruses differ in external structure and which type of molecule (RNA or DNA) carries their genetic information (genome). At the moment, the FDA has approved vaccines for HAV and HBV. One type of HEV vaccine* has been licensed in China11.

HBV was one of the first viruses linked to cancer12. In 1965, the American physician Baruch Blumberg, discovered a little piece of hepatitis B virus in the blood of a patient with “yellow jaundice”, now known as hepatitis. He later developed a diagnostic test and vaccine, earning the Nobel Prize in 197613.

HBV and HCV are now considered the most common risk factors for liver cancer worldwide14. HBV is more infectious and more stable than HCV, and even if most adults recover completely from an HBV infection within a few months, when the infection does persist it may lead to liver cancer.

Chronic HBV infection can promote cancer formation through a combination of direct and indirect mechanisms. Like HPV, HBV can insert its DNA into the instruction manual of the host cell and mess with normal cell growth. Chronic infection also leads to increased liver inflammation that can kill liver cells and form scar tissue (fibrosis). Over time, this can progress to cirrhosis, where the liver becomes severely scarred, impairing its normal function15. In response to this damage, the liver tries to regenerate, increasing cell division and DNA replication – a process that increases the chances of mutations and the development of cancerous cells.

HBV vaccine: First of its kind

The first hepatitis B vaccine, approved in 1981, was the world’s first preventive cancer vaccine16. Today, several highly effective HBV vaccines are available, administered as either two or three doses, depending on the vaccine brand17. In the United States, the FDA has licensed three vaccines against HBV only (Engerix-B, Heplisav-B, and Recombivax HB), and other combination vaccines against multiple diseases: Twinrix (hepatitis A and B), Pediarix (diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, hepatitis B, and poliomyelitis), and Vaxelis (diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, poliomyelitis, hepatitis B, and Haemophilus influenzae type b).

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that all infants receive a first dose within 24 hours of birth, followed by additional doses. Since these vaccines provide long-lasting protection – potentially lifelong protection against HBV – booster doses are generally not required for healthy adults. There are exceptions for certain groups, such as health care workers, for whom WHO recommends vaccination to reduce the risk of infection in medical settings18.

Currently, there are no commercially available vaccines against HCV, but several FDA-approved antiviral drugs can eliminate HCV infections by blocking specific proteins that the virus needs to reproduce. No vaccines have been approved for HDV either. However, thanks to its “interdependent relationship” with HBV, hepatitis B vaccination also protects against HDV infection!

HBV and HPV vaccines effectiveness in numbers

Since the introduction of HBV and HPV vaccines, these tools have helped prevent hundreds of thousands of cancer cases and deaths worldwide in countries with immunization programs. In particular, HBV vaccination has significantly decreased the transmission of HBV with a consequent decrease in liver cancer. One modelling study performed in 98 low- and middle-income countries, estimates that HBV vaccination will prevent 38 million deaths among those born between 2000 and 203019.

Strikingly, HPV vaccinations have been proven almost 100% effective against the targeted HPV infections20. Since nearly all cervical cancers are caused by HPV21, vaccines – together with HPV screening programmes – become a key tool in the WHO’s global strategy to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health threat22. Overall, continued efforts to expand vaccination coverage and develop vaccines for other cancer-associated infections hold promise for further reducing the global cancer burden. Due to health care cost reduction, low risk and high efficacy, preventing cancer before it starts remains one of the most powerful tools not only in oncology23, but across all public health policies24.

Talk to your doctor about HPV and HBV vaccines

You can find more information about:

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines here

Hepatitis B virus vaccines here

Countries that include HPV vaccines in their national vaccination programs here

Countries that include HBV vaccines in their national vaccination programs here

- International Agency for Research on Cancer_WHO (n.d.) 12 ways to reduce your cancer risk. Vaccination and infections. Cancer-code-europe.iarc. Retrieved June 15th 2025 from https://cancer-code-europe.iarc.fr/index.php/en/ecac-12-ways/vaccination-recommendation. ↩︎

- American Cancer Society. (21 March 2023) Viruses that Can Lead to Cancer. Cancer.org. Retrieved June16th 2025 from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/risk-prevention/infections/infections-that-can-lead-to-cancer/viruses.html. ↩︎

- NIH National Cancer Institute (30 April 2025) HIV Infection and Cancer Risk. cancer.gov Retrieved June22nd 2025 from https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/infectious-agents/hiv-fact-sheet#:~:text=breast%20(17).-,Has%20the%20introduction%20of%20antiretroviral%20therapy%20changed%20the%20cancer%20risk,living%20with%20HIV%20(7). ↩︎

- American Cancer Society. (30 April 2024) Types of HPV. Cancer.org. Retrieved June17th 2025 from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/risk-prevention/hpv/types-of-hpv.html. ↩︎

- Lowy DR. Harald zur Hausen (1936 to 2023): Discoverer of human papillomavirus infection as the main cause of cervical cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024 Mar 12;121(11):e2400517121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2400517121. Epub 2024 Mar 4. PMID: 38437560; PMCID: PMC10945753. ↩︎

- Jensen, J.E.; Becker, G.L.; Jackson, J.B.; Rysavy, M.B. Human Papillomavirus and Associated Cancers: A Review. Viruses 2024, 16, 680. https://doi.org/10.3390/v16050680. ↩︎

- Graham SV. The human papillomavirus replication cycle, and its links to cancer progression: a comprehensive review. Clin Sci (Lond). 2017 Aug 10;131(17):2201-2221. doi: 10.1042/CS20160786. PMID: 28798073. ↩︎

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (31 January 2025) About Genital HPV Infection. cancer.gov Retrieved June20th 2025 from https://www.cdc.gov/sti/about/about-genital-hpv-infection.html#:~:text=About%20Genital%20HPV%20Infection%20*%20Human%20papillomavirus,fact%20sheet%20answers%20basic%20questions%20about%20HPV. ↩︎

- American Cancer Society. (30 April 2024) HPV vaccines. Cancer.org. Retrieved June21st 2025 from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/risk-prevention/hpv/hpv-vaccines.html. ↩︎

- World Health Organization (1 September 2019) Hepatitis. who.int. Retrieved June 16th 2025 from https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/hepatitis. ↩︎

- World Health Organization (10 April 2025) Hepatitis E. who.int. Retrieved June18th 2025 from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-e#:~:text=Additionally%2C%20the%20development%20of%20the,populations%20and%20curb%20disease%20outbreaks. ↩︎

- Arbuthnot P, Kew M. Hepatitis B virus and hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Exp Pathol. 2001 Apr;82(2):77-100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2001.iep0082-0077-x. PMID: 11454100; PMCID: PMC2517704. ↩︎

- Stroffolini T, Stroffolini G. A Historical Overview on the Role of Hepatitis B and C Viruses as Aetiological Factors for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Apr 20;15(8):2388. doi: 10.3390/cancers15082388. PMID: 37190317; PMCID: PMC10136487. ↩︎

- American Cancer Society. (11 February 2025) Liver Cancer Risk Factors. Cancer.org. Retrieved June17th 2025 from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/liver-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html ↩︎

- Levrero M, Zucman-Rossi J. Mechanisms of HBV-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2016 Apr;64(1 Suppl):S84-S101. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.02.021. PMID: 27084040. ↩︎

- Hepatitis B Fountation (n.d.) Hepatitis B Vaccine History. hepb.org Retrieved June17th 2025 from https://www.hepb.org/prevention-and-diagnosis/vaccination/history-of-hepatitis-b-vaccine/. ↩︎

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (31 January 2025) Hepatitis B Vaccine. cancer.gov Retrieved June 19th 2025 from https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis-b/vaccination/index.html. ↩︎

- World Health Organization (July 2017) WHO position papers on Hepatitis B . who.int. Retrieved June 16th 2025 from https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/policies/position-papers/hepatitis-b. ↩︎

- Li et al.Estimating the health impact of vaccination against ten pathogens in 98 low-income and middle-income countries from 2000 to 2030: a modelling study. The Lancet Volume 397, Issue 10272, 30 January–5 February 2021 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32657-X. ↩︎

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (16 November 2021) About HPV Vaccines. cancer.gov Retrieved June20th 2025 from https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/hpv/hcp/vaccines.html. ↩︎

- NIH National Cancer Institute (2 August 2024) Cervical Cancer Causes, Risk Factors, and Prevention. cancer.gov Retrieved June22nd 2025 from https://www.cancer.gov/types/cervical/causes-risk-prevention. ↩︎

- World Health Organization 2020. Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem ISBN 978-92-4-001410-7 https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/336583/9789240014107-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. ↩︎

- Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (24 February 2025) Preventing Cancer: The Far-Reaching Impact of Vaccines. publichealth.jhu.edu Retrieved June21st 2025 from https://publichealth.jhu.edu/ivac/2025/preventing-cancer-the-far-reaching-impact-of-vaccines. ↩︎

- Caron RM, Noel K, Reed RN, Sibel J, Smith HJ. Health Promotion, Health Protection, and Disease Prevention: Challenges and Opportunities in a Dynamic Landscape. AJPM Focus. 2023 Nov 8;3(1):100167. doi: 10.1016/j.focus.2023.100167. PMID: 38149078; PMCID: PMC10749873. ↩︎

© 2025 WithinOncology. All rights reserved.

This article, including all text, tables, and figures, is the intellectual property of WithinOncology and its contributors. Unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or use of any content without explicit written permission is strictly prohibited. For inquiries, please contact us via the contact form.

Leave a comment