KRAS was one of the first oncogenes identified in human cancers in the early 1980s. It remains the most commonly mutated oncogenic driver across multiple cancer types and plays a critical role in regulating cellular growth and survival. As previously described, mutant KRAS is like a broken accelerator that endlessly drives growth and survival, leading to the unlimited cell growth that defines cancer. Although KRAS mutations are found in approximately 10% of all carcinomas, their prevalence and specific subtypes vary significantly among tumor types1. The highest frequency is observed in pancreatic cancer, where 81% of patients harbor KRAS mutations. Colorectal cancer follows with a mutation rate of 37%, and lung cancer exhibits KRAS mutations in approximately 21% of cases. These mutations are often associated with a poor prognosis, contributing to more aggressive disease progression and resistance to treatment. The high frequency of KRAS mutations and their prevalence in pancreatic cancer make them an attractive therapeutic target for pharmaceutical development, offering the potential to kill “multiple birds” with one stone.

The Molecular Switch KRAS

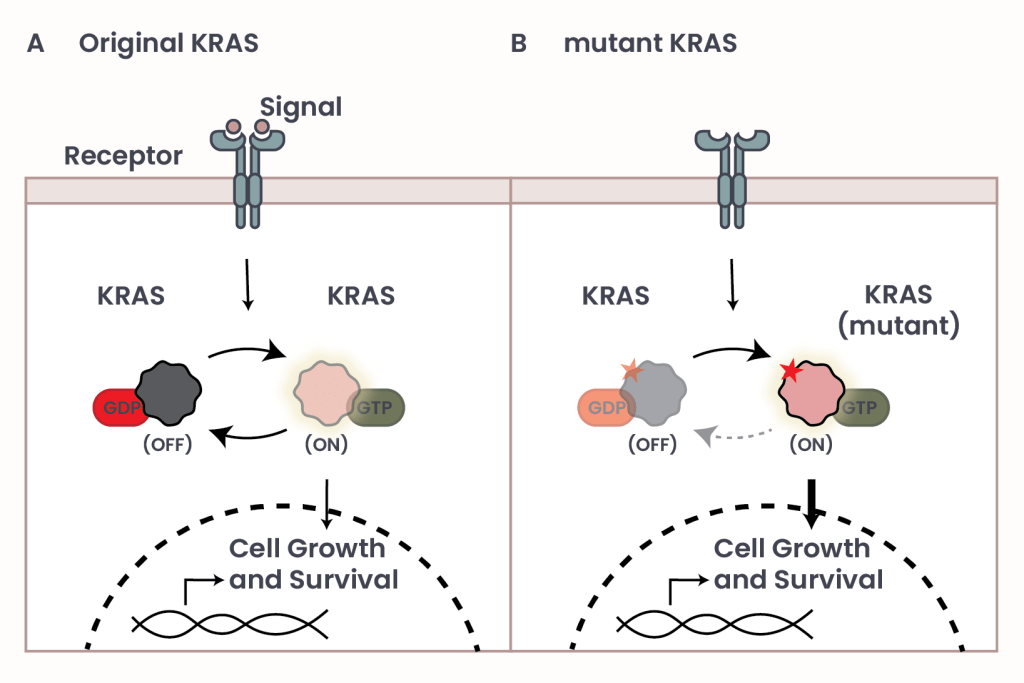

Figure 1: The effect of mutations in the molecular switch KRAS.

KRAS functions like a molecular switch that turns cell growth on and off. Normally, KRAS is “off” until the cell receives a signal – like a green light – from outside. When that happens, KRAS turns on by swapping out a small molecule called GDP for another one called GTP. This change activates a chain of messages inside the cell, called “signaling pathway”, telling it to grow and survive. Once the signal stops, KRAS turns off again (Figure 1, panel A).

However, mutations in KRAS – typically small changes known as point mutations – can drastically alter its structure. Point mutations are like typos in our DNA, and even the change of a small letter can make a big difference (like “cut” and “cat”)! In many cancers, these mutations lock KRAS in the “on” position, causing continuous growth signals even in the absence of external cues (Figure 1, panel B). Among the 21 known KRAS mutations, the three most common are called G12D (29.19%), G12V (22.97%), and G12C (13.43%), each significantly contributing to cancer progression. Proteins consist of chains of molecules called ‘amino acids’, the basic building block unit of proteins. The specific mutations mentioned above are like labels that describe exactly where the typo, or mutation, happens and what it changes: ‘G12′ refers to the 12th amino acid position in the protein, where normally there’s a glycine (G). In these mutations, glycine is swapped for a different amino acid – D stands for aspartic acid, V for valine, and C for cysteine – changing how the protein is built.

However, mutations in KRAS – typically small changes known as point mutations – can drastically alter its structure. Point mutations are like typos in our DNA, and even the change of a small letter can make a big difference (like “cut” and “cat”)! In many cancers, these mutations lock KRAS in the “on” position, causing continuous growth signals even in the absence of external cues (Figure 1, panel B). Among the 21 known KRAS mutations, the three most common are called G12D (29.19%), G12V (22.97%), and G12C (13.43%), each significantly contributing to cancer progression. Proteins consist of chains of molecules called ‘amino acids’, the basic building block unit of proteins. The specific mutations mentioned above are like labels that describe exactly where the typo, or mutation, happens and what it changes: ‘G12′ refers to the 12th amino acid position in the protein, where normally there’s a glycine (G). In these mutations, glycine is swapped for a different amino acid – D stands for aspartic acid, V for valine, and C for cysteine – changing how the protein is built.

Therapeutic Advancements in Targeting KRAS mutations

For over three decades, KRAS mutations were deemed “undruggable” due to the inherent challenges in designing molecules that could inhibit its function. To work properly, a drug needs to stick tightly and specifically to its target, like a key fitting perfectly into a lock. But KRAS had some tricky features that make this especially challenging:

- KRAS is constantly switching between “off” and “on” states, which makes it tough for drugs to lock onto it long enough to shut it down.

- When it’s in the “on” state, KRAS holds very tightly to the activating GTP molecule – so strong that a drug can’t easily push it out of the way.

- For a long time, scientists didn’t fully understand the shape of KRAS, which made it hard to find the right spot where a drug could fit and block its activity.

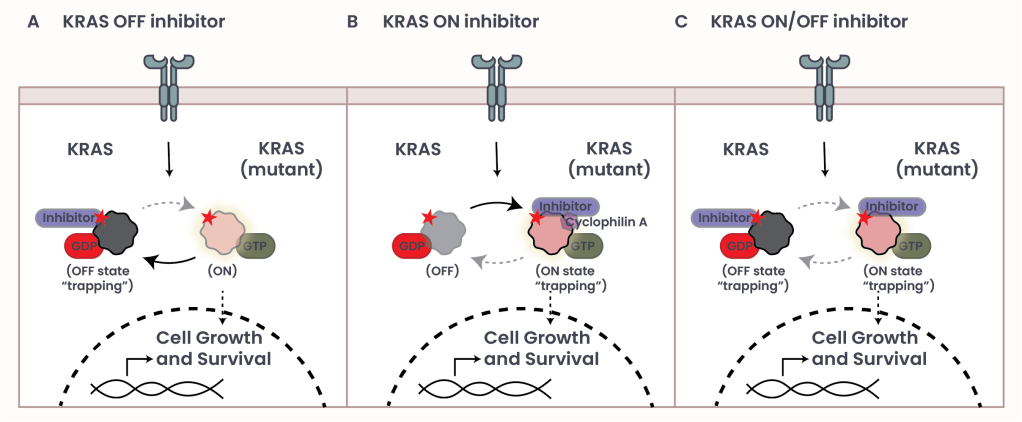

Recent technological advancements have led to the development of the first KRAS inhibitors – Sotorasib and Adagrasib – which specifically target the G12C mutation by locking KRAS in its inactive state (KRAS OFF inhibitor) (see Figure 2, panel A).

- Sotorasib (by Amgen) received FDA approval in 2021 following the Phase 1/2 CodeBreaK 100 trial in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who had received at least one prior systemic therapy (NCT03600883)2. The drug achieved an overall response rate (ORR) of 36%, with 81% of patients experiencing disease control – defined as complete response, partial response, or stable disease for more than three months. The median duration of response (DoR) was 10 months. Common adverse events included diarrhea, musculoskeletal pain, nausea, fatigue, hepatotoxicity, and cough.

- Adagrasib (by Bristol Myers Squibb) was FDA-approved in 2022 based on results from the Phase 1/2 KRYSTAL-1 study (NCT03785249) involving patients with advanced solid tumors – including pancreatic, gastrointestinal, breast, ovarian cancers, and glioblastoma – harboring the KRAS G12C mutation3. The ORR was 35%, with a median DoR of 5 months. Reported side effects included nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and fatigue.

For patients with advanced solid tumors who have progressed beyond first-line therapies, these KRAS G12C inhibitors mark a significant breakthrough, offering new hope in an area of previously limited treatment options.

Figure 2: Inhibitors of mutant KRAS

The Evolving Landscape of KRAS Inhibition

Despite the clinical success of KRAS G12C inhibitors, many patients eventually develop resistance through the acquisition of additional mutations that restore downstream messages that lead to cell growth. The emergence of multiple secondary mutations, not just one, in response to therapy shows how much certain cancers rely on KRAS for survival4.

Given KRAS’s central role and the complexity of targeting it, it is unsurprising that numerous pharmaceutical companies are now developing next-generation inhibitors, including those that target other KRAS mutations like G12D and G12V5. These investigational agents aim to improve selectivity (the ability to inhibit KRAS and no other protein), potency (the strength to inhibit KRAS fully and not just partially), and to overcome resistance through novel mechanisms of action, including:

- KRAS ON inhibitors, which bind the active, GTP-bound form of KRAS in conjunction with Cyclophilin A and block messaging, despite being in the ‘on’ state (see Figure 2, panel B).

- KRAS ON/OFF inhibitors, which target KRAS regardless of its activation state (see Figure 2, panel C).

- Pan-KRAS inhibitors, designed to inhibit KRAS across multiple mutation subtypes, offering therapeutic potential for a wider range of KRAS-driven cancers especially for those with less common KRAS alterations.

In addition, combination therapies are being explored to enhance efficacy and prevent resistance by targeting multiple pathways simultaneously6.

Our ability to drug the “undruggable,” KRAS being the example here, gives hope for turning the list of previously so-called “undruggable” proteins into actionable targets. Thus, KRAS inhibitors represent a landmark in oncology drug development – transforming a long-considered “undruggable” target into a viable and evolving therapeutic frontier. While challenges remain, continued innovation in this space offers renewed hope for patients with KRAS-driven cancers and sets the stage for more durable and broadly effective treatment strategies.

- Yang Y, Zhang H, Huang S, Chu Q. KRAS Mutations in Solid Tumors: Characteristics, Current Therapeutic Strategy, and Potential Treatment Exploration. J Clin Med. 2023 Jan 16;12(2):709. doi: 10.3390/jcm12020709. PMID: 36675641; PMCID: PMC9861148. ↩︎

- Amgen. (28 May, 2021), FDA Approves LUMAKRAS™ (Sotorasib), The First And Only Targeted Treatment For Patients With KRAS G12C-Mutated Locally Advanced Or Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. amgen.com. Retrieved May 20 2025 from https://www.amgen.com/newsroom/press-releases/2021/05/fda-approves-lumakras-sotorasib-the-first-and-only-targeted-treatment-for-patients-with-kras-g12cmutated-locally-advanced-or-metastatic-nonsmall-cell-lung-cancer ↩︎

- Shubham Pant et al. KRYSTAL-1: Activity and safety of adagrasib (MRTX849) in patients with advanced solid tumors harboring a KRASG12C mutation.. JCO 41, 425082-425082(2023).

DOI:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.36_suppl.425082 ↩︎ - Singhal A, Li BT, O’Reilly EM. Targeting KRAS in cancer. Nat Med. 2024;30(4):969-983. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-02903-0 ↩︎

- Oya Y, Imaizumi K, Mitsudomi T. The next-generation KRAS inhibitors…What comes after sotorasib and adagrasib?. Lung Cancer. 2024;194:107886. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2024.107886 ↩︎

- Perurena N, Situ L, Cichowski K. Combinatorial strategies to target RAS-driven cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2024;24(5):316-337. doi:10.1038/s41568-024-00679-6 ↩︎

© 2025 WithinOncology. All rights reserved.

This article, including all text, tables, and figures, is the intellectual property of WithinOncology and its contributors. Unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or use of any content without explicit written permission is strictly prohibited. For inquiries, please contact us via the contact form.

Leave a comment