After starting our car, we hit the gas pedal, or accelerator, to begin moving. When a sea of red lights appears ahead of us on the freeway, we slam on the brakes to slow down. Our cells prevent cancer similarly. Through the actions of tumor suppressor genes, our cells’ brakes, cancer formation is limited. Proto-oncogenes, our cells’ gas, promote cell growth in a controlled manner, but if mutated can turn into oncogenes which endlessly promote cell growth. Thus, cancer is a result of failed brakes and hyperactive accelerators within our cells. Like a brake line getting cut, or the gas pedal getting stuck, loss or alteration of regulatory functions have the potential to lead to a catastrophic pileup of cells in our body: cancer.

Broken cellular brakes and accelerators

Despite its small size, cells are significantly more complex than a car – cars have around 30,000 parts, while cells contain around 42 million proteins! Just like parts of a car breaking down, our cells can also get damaged and need repair. Genes, part of our DNA, instruct the cell when, how, and how many proteins must be made, and can get “broken” in the form of DNA mutations. Gene mutations could lead to different outcomes, including too little or too much protein, and altered protein function resulting in too little or too much protein activity. Our proteins control the various actions of a cell. Gene mutations that affect protein function or abundance can lead to actions performed incorrectly, at the wrong time, or too frequently.

Just as we may rear-end someone if our brakes don’t work, or our gas doesn’t let up, improper balance between tumor suppressors and proto-oncogenes can drive cancer. Tumor suppressors act like brakes for cancer by limiting DNA mutations and cell growth. As their name implies, tumor suppressors are critical for tumor prevention, and without them the likelihood of cancer increases. On the other hand, proto-oncogenes fuel regular cell growth and survival, but in a balanced manner, like accelerators. If mutated, proto-oncogenes may become oncogenes and lose their balanced activity and endlessly promote growth and survival, leading to the unlimited cell growth that defines cancer.

Cells careen towards cancer without tumor suppressors

Tumor suppressors act through a variety of mechanisms, including: minimizing mutations, limiting cell growth, and activating cell death (apoptosis) if irregular activities are noticed1.

As described above, DNA mutations can fuel cancer. Mutations can arise following DNA damage. Just as we can identify and repair damage to cars, cells can repair damage to DNA. Due to the complexity of cells, DNA repair is a complicated process and can easily go wrong. Mutations can occur when DNA is not fully repaired. By promoting accurate repair, especially in tumor suppressors and proto-oncogenes, tumor suppressors prevent cancer. If a mutation is acquired, cells try to limit the spread of that mutation by limiting cell growth.

One cell multiplies to two through a process highly regulated by tumor suppressors called, ironically, cell division. Cells first grow in size and duplicate their internal components, then divide into two new cells where the process begins again. Many self-checks are performed throughout cell division to ensure the cell is healthy. Similarly, car parts are mass produced, and quality controls ensure accuracy. Loss of quality control may lead to damaged parts being widely installed in cars. Cellular self-checks, called checkpoints, respond to abnormalities by arresting the cell cycle, stopping cell growth in its tracks. Cell cycle arrest through checkpoint activation gives cells time to address the problem before dividing.

In worse-case scenarios, checkpoints can also trigger cell death. When a car is totaled, it is often scrapped for parts. When a cell is excessively damaged, or critical cellular processes have been compromised, it can activate its own scrapping through apoptosis, or other cell death mechanisms. If apoptosis genes are lost or mutated, damaged and potentially cancerous cells are allowed to propagate.

p53: the guardian of the genome

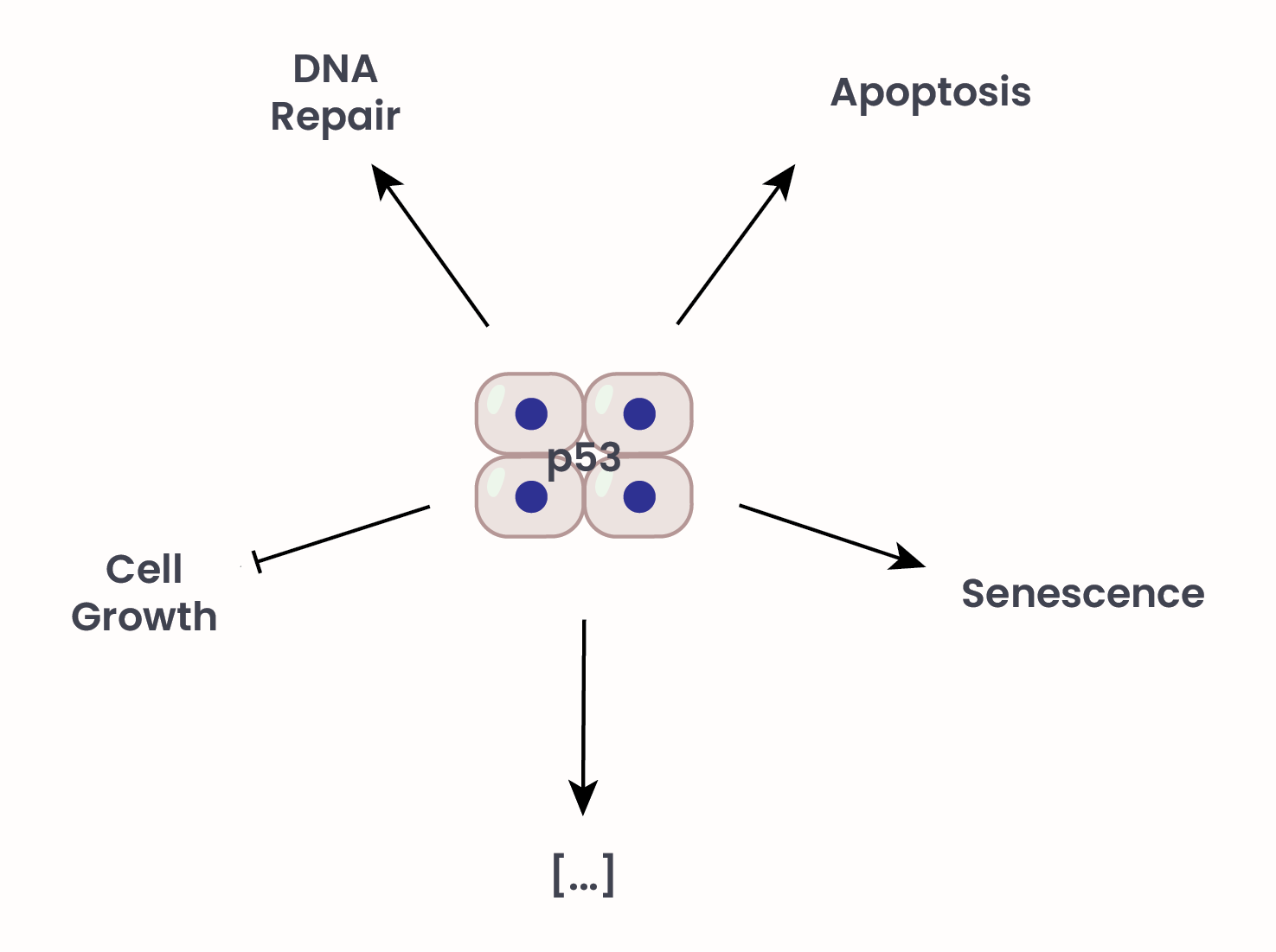

The most well-known tumor suppressor gene is TP53 – also known as the guardian of the genome. The TP53 protein product p53 resides around DNA, and drives expression of numerous genes that slow cell growth, promote DNA repair, activate apoptosis, and more (Figure 1). Due to its widespread activity in limiting tumor growth, TP53 mutations are the most common in cancer, present in around one in three cases2.

Figure 1. p53 functions. p53 supports numerous tumor suppressive cellular activities, including activation of senescence, an anti-cancer cell state in which cell growth is permanently inhibited.

Taking the ‘proto’ out of proto-oncogene

A proto-oncogene is a “potentially dangerous” gene and becomes a cancer-driving oncogene if it is mutated in a way that leads to excessive protein activity3. Proto-oncogene function is often activated by internal and external signals. A car may run out of control if the gas pedal is stuck down, or there are other issues that lead to the gas pedal ‘signal’ being constantly read by the engine. For cells, these signals are small molecules or proteins. Upon recognition of the signal, proto-oncogenes ‘turn on’ and promote cell growth or survival. Mutations of proto-oncogenes can result in permanent ‘on’ states in the absence of activating signals, producing an oncogene that excessively activates cell growth and survival.

The crassnes of mutated KRAS

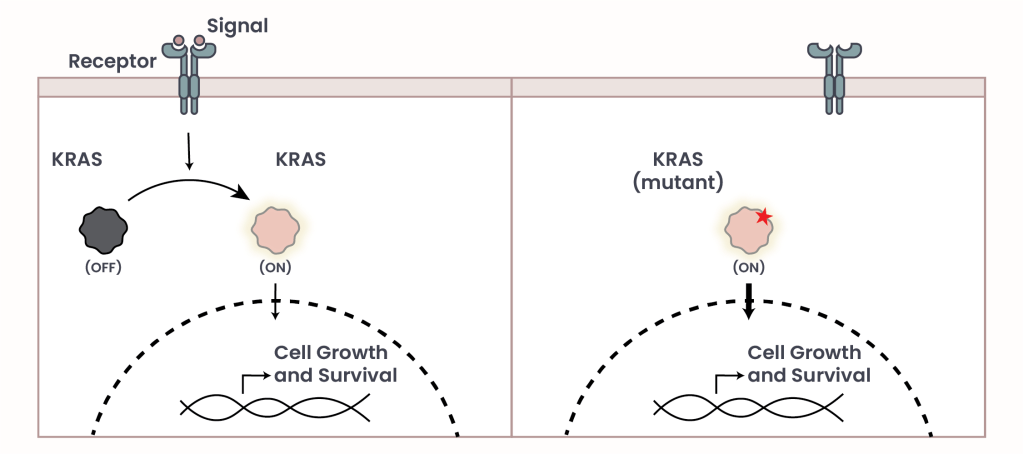

KRAS is one of the most well-known proto-oncogenes, and is mutated into an oncogene in one in ten cancers2. KRAS protein normally resides inside our cells in an “off” state, but it can be turned “on” when it receives external signals from receptors – a sort of antenna present on the surface of the cell (Figure 2). Putting your foot onto the accelerator is like an external signal connecting to a receptor, while KRAS would be the essential component that transmits that information to the engine.

Figure 2. KRAS activation and outcome of mutant KRAS.

Turning KRAS on tells the cell “go!”, resulting in growth and survival. Mutations can lead to KRAS permanently being on and constantly activating growth and survival regardless of the presence of the activating signal – like your car accelerating without putting your foot on the pedal. Among many other oncogenes, KRAS was once considered ‘undruggable,’ impossible to hit with a specific drug, however research into its targeting has seen increasing success in recent years, and will be discussed in an upcoming Within Progress article4.

Extending knowledge to extend life

We built cars from scratch and quite literally wrote the book on how they work. With painstaking research, we have been slowly reverse engineering a similar book of how biology, including cancer, works. Just like brake failure having a variety of causes, tumor suppressors can fail to suppress cancer through a variety of mechanisms. These genes are similar in that they limit cancer, and their mutation or loss promotes cancer. Conversely, proto-oncogenes support cell growth and survival in a regulated manner, but can be mutated into deregulated oncogenes that fuel cancer growth. The discovery and characterization of cancer-driving genes have not only taught us a great deal about how cancer is formed and progresses, but also increased our understanding of how cells and life work, and gave us therapeutic avenues. Mutations impairing tumor suppressor and proto-oncogene function can sometimes be targeted with drugs, restoring healthy cellular functions. Numerous drugs to extend or save lives are already available, and even more are in the pipeline.

- Joyce C, Rayi A, Kasi A. Tumor-Suppressor Genes. Updated 28 Aug 2023. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved April 20 2025 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532243/. ↩︎

- Mendiratta, G., Ke, E., Aziz, M. et al. Cancer gene mutation frequencies for the U.S. population. Nature Communications, Volume 12, Article 5961 (2021). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-26213-y ↩︎

- American Cancer Society. (Revised 31 Aug. 2022), Oncogenes, Tumor Suppressor Genes, and DNA Repair Genes. Cancer.org. Retrieved April 20 2025 from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/understanding-cancer/genes-and-cancer/oncogenes-tumor-suppressor-genes.html ↩︎

- Parikh, K., Banna, G., Liu, S.V. et al. Drugging KRAS: current perspectives and state-of-art review. Journal of Hematology & Oncology, Volume 15, Article 152 (2022). DOI: 10.1186/s13045-022-01375-4 ↩︎

© 2025 WithinOncology. All rights reserved.

This article, including all text, tables, and figures, is the intellectual property of WithinOncology and its contributors. Unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or use of any content without explicit written permission is strictly prohibited. For inquiries, please contact us via the contact form.

Leave a comment