What cancer and wildfires have in common, and how we detect them

Cancer is insidious. It often starts as innocuous as a small flame burning in a remote forest – more likely to sputter out than grow. Like cancer, a fire left to its own devices, and in the right conditions, can grow to a roaring wildfire. The name of the game is thus early detection. Catching both cancer and fire early on can minimize damage done, but the more critical reason for early detection is that as each grows, they become harder to stop. So, how do we detect these unwelcome invaders before they get out of control?

Early efforts for early detection

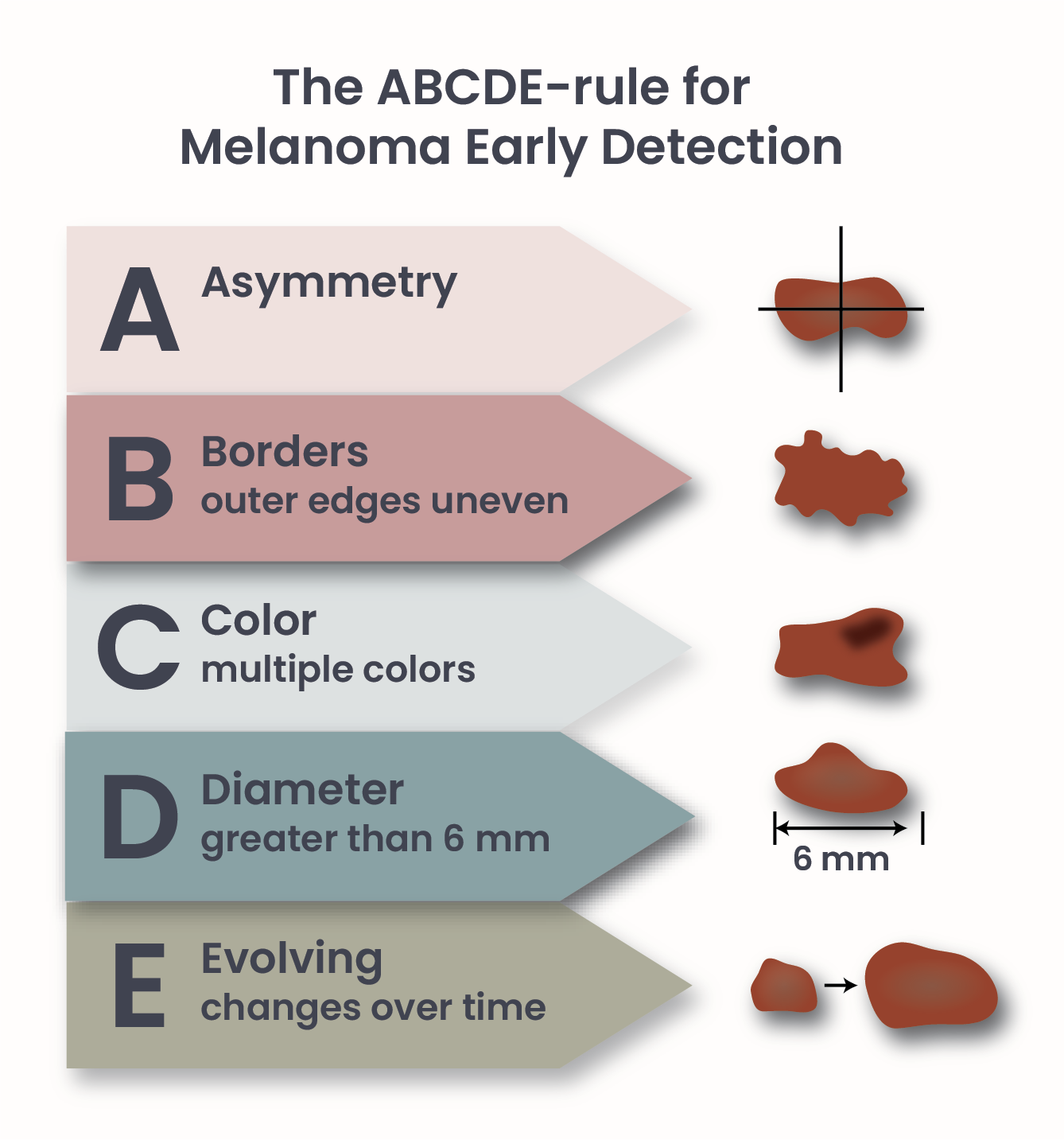

The appearance of cancer symptoms suggests the cancer has already grown enough to cause harm, just like smelling smoke means you’re already in danger. To detect fires before experiencing their havoc, the US forest service initially built lookout towers to visually identify wildfires1, akin to detecting cancer via self examination. During a self examination, skin (Figure 1), breast, testicle, and oral cancer may be detected as abnormal skin or lumps2. Prostate cancer can be detected by a medical professional through a digital rectal exam, in addition to other more advanced methods3. Those screening methods will not work for all incidences of these cancers, and other types are not usually detected physically before becoming symptomatic, calling for improved methods of tumor visualization.

Figure 1. ABCDE-rule for Melanoma early detection.

Pictures tell a thousand words

We started using planes as fire spotters, and eventually satellites were enlisted as well. Then, we improved our ability to analyze satellite images1. This march of intellect has been mirrored in the improvement of cancer detection methods: advancements in biomedical imaging have given us tools to detect abnormal growths deep in our body. Medical imaging works similarly to shining a light on your hand and making a shadow puppet appear on a wall. By exposing a part of the body to energy sources, like X-rays an image based on the “shadow” the energy casts through our organs and tissues can be computed4. These analyses are expensive, and require significant time and skill. Detecting cancer with imaging techniques is thus usually performed on individuals that are at high risk to develop cancer – but how do we know who is at high risk?

Learning from the past

Researching historical fire records has allowed us to more accurately predict where and when they may occur. Similarly, the discovery that cancer can be inherited via mutated DNA passed down from parents5 represented a much needed boon for the field. This allowed for the calculation of cancer risk based on familial cancer incidence. Although screening an entire population with imaging is not cost-effective, screening high-risk individuals is. Numerous cancers can be detected in this way, but not all.

Time for an upgrade

Despite our best efforts, fires spread across large swathes of land year in and year out across the world. Evidently, not all fires can be predicted, nor detected before they become serious hazards. Cancers can also become deadly without being detected. Pancreas tissue, for example, is often obscured by other organs6, resulting in difficulties identifying tumors. Additionally, liquid cancers, such as leukemia and lymphoma, do not form solid masses and thus are not detectable via imaging. Cancers can also develop from new mutations not present in either parent, which cannot be predicted, such as childhood leukemia7.

Novel methods of screening capable of simultaneously detecting multiple cancers at earlier stages are required to improve our cancer detection game. To be amenable to widespread testing, these new methods must be affordable, quick, and (relatively) simple to apply.

How to spot the signs of cancer

All cells in our body continually release molecules – and cancer cells are no different . Imagine an experienced tracker following an animal through a forest, knowing where it went based on the unique fur, footprints, and damage to foliage left behind. The identity and quantity of molecules, or signals, released changes based on cell type. For example, neurons and bone cells are very different, and thus likely release distinct signals. These circulating molecules often take the form of DNA, called cell-free DNA (cfDNA), or proteins8. Although cancer and healthy cells are largely similar, decades of research, and updated technologies, have allowed us to distinguish between their signals.

The future of early cancer detection

Multi Cancer Early Detected (MCED) tests represent the next generation of cancer detection. MCED tests consist of blood tests for cancer signals. Multiple cancer molecules can be detected in a single test, allowing for the simultaneous detection of many signals. Imagine being able to sample the air periodically, throughout the country, to detect fires before satellites can take a picture of them – that is what the future of MCED tests may look like for the world of oncology.

Drawing a blood sample does not require the same level of technical knowledge that operating biomedical imaging devices requires. There is also a considerable difference in patient time needed: while a blood draw takes a few minutes, imaging can take several minutes or over an hour. The equipment for imaging devices is also extremely expensive, and thus may require a longer trip to hospitals, and may not be available in certain communities. Analysis of blood tests, on the other hand, often requires less expensive machines, and because one machine can process numerous samples a single analysis does not monopolize precious machine time like an imaging device does. Blood draws also carry less risk than imaging, as exposure to the energy used, such as X-rays, can be harmful.

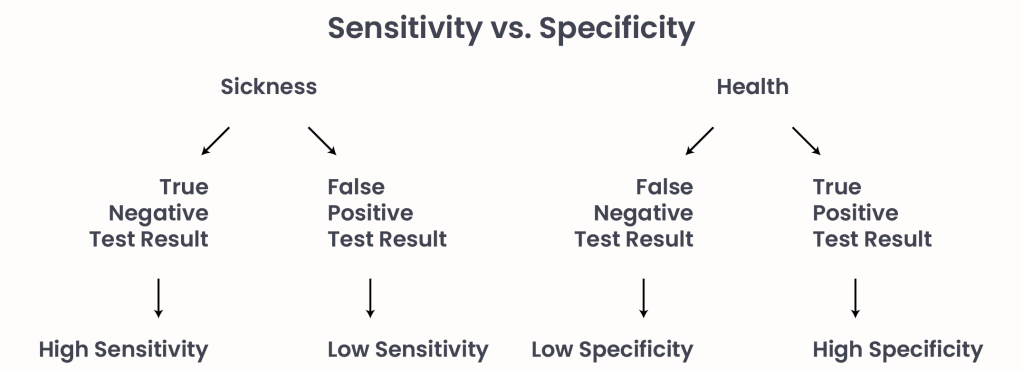

Figure 2. Sensitivity vs. Specificity in medical testing.

As cancers progress they release more and more signals and become easier to detect, while early stage cancers may go undetected. Tests must be sensitive enough to detect even low levels of cancer signals released during early stages, thereby detecting all incidences of cancer. Tests must also be specific, meaning that they determine a healthy individual is indeed healthy. A test with low sensitivity would determine that a cancer patient is healthy, while a test with low specificity would determine that a healthy person has cancer (Figure 2).

MCED are currently complementary to traditional methods of cancer detection. These blood tests may one day fulfill our need for early detection entirely, but further research is required to achieve that reality. Luckily, numerous endeavors are active across the world to develop new MCED tests to give everybody a fighting chance through early detection.

- NASA. (April 29, 2019), Building a Long-Term Record of Fire. nasa.gov. Retrieved March 8 2025 from https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/145421/building-a-long-term-record-of-fire. ↩︎

- Indiana department of Health. (n.d.), Self Screening. dph.illinois.gov. Retrieved March 8 2025, from https://dph.illinois.gov/topics-services/life-stages-populations/mens-health/self-screening.html. ↩︎

- Mayo Clinic. (20 Feb. 2025), Prostate Cancer. mayoclinic.com. Retrieved March 8 2025 from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/prostate-cancer/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20353093. ↩︎

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering. (June 2022), X-rays. Retrieved March 10 2025 from http://www.nibib.nih.gov/science-education/science-topics/x-rays. ↩︎

- National Cancer Institute. (8 Aug. 2024), The Genetics of Cancer. Cancer.gov. Retrieved March 10 2025 from http://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/genetics. ↩︎

- Johns Hopkins Medicine; Jin He. (n.d.), Pancreatic Cancer Diagnosis. hopkinsmedicine.org. Retrieved March 10 from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/pancreatic-cancer/pancreatic-cancer-diagnosis. ↩︎

- Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. (n.d.), Pediatric Leukemias. chop.edu. Retrieved March 10 2025 from https://www.chop.edu/conditions-diseases/pediatric-leukemias. ↩︎

- Nature; Michael Eisenstein. (n.d.), Putting early cancer detection to the test. nature.com. Retrieved March 10 2025 from https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-00530-4. ↩︎

© 2025 WithinOncology. All rights reserved.

This article, including all text, tables, and figures, is the intellectual property of WithinOncology and its contributors. Unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or use of any content without explicit written permission is strictly prohibited. For inquiries, please contact us via the contact form.

Leave a comment