Our bodies defend against attacks from various external sources, such as bacteria and viruses. In order to differentiate between our own cells, and invaders such as bacteria and viruses, our cells recognize non-self entities. Through medical and biological research, we have learned how to aid in the biological defense process. Various antibiotics and antivirals have been developed as a result. Successful treatments rely on the ability to specifically target foreign invaders in our body – harming both our own cells and the invaders would result in significant side effects.

Cancer, however, comes from our own cells that have changed in various ways. Cancer cells grow uncontrollably, and move through our body. Both doctors, and our own bodies, have a harder time differentiating between cancer and healthy cells, than between bacteria or viruses and healthy cells. How does cancer occur? How can we target cancer cells despite their similarity to healthy cells? As cancer comes from our own cells, understanding how regular cells function is critical to know how cancer cells work. We can think of the processes a cell performs as similar to the process a chef follows to cook.

How one cell becomes thirty trillion

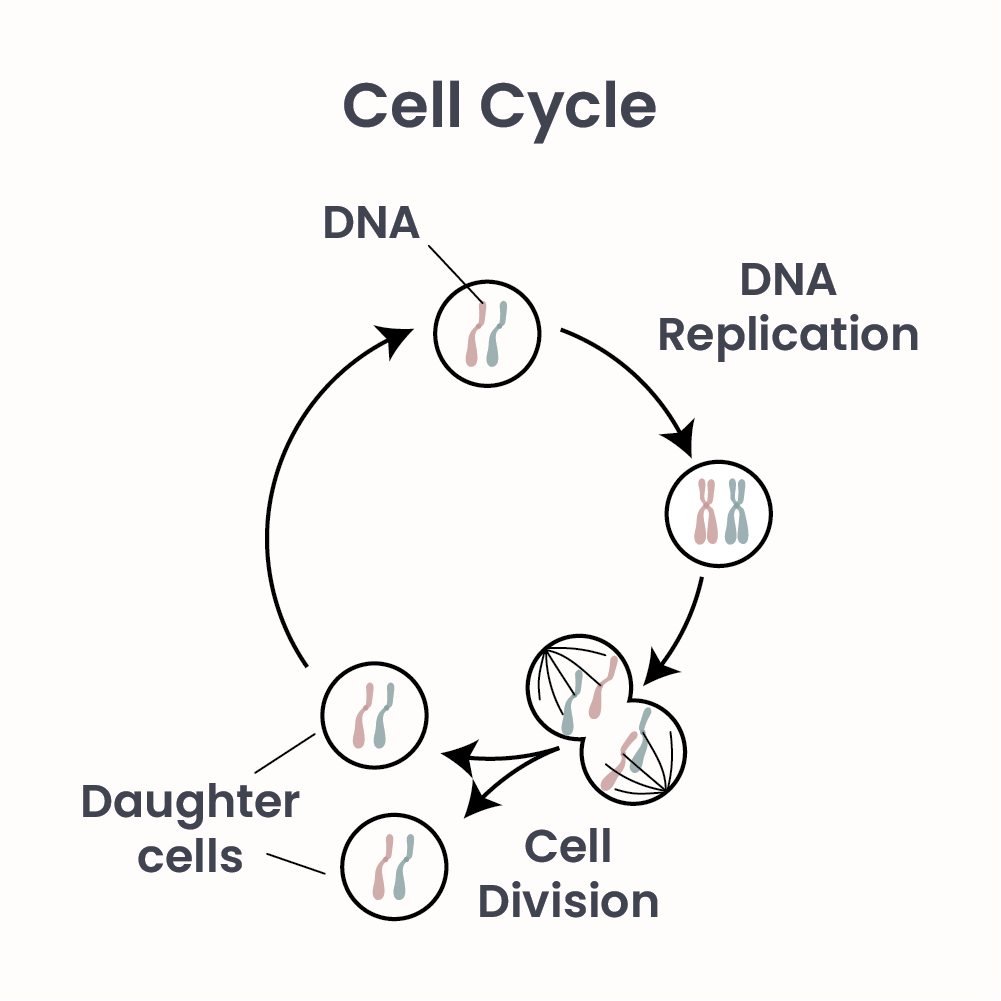

Just like chefs following detailed recipes to create rich sauces and intricate dishes, our cells have their own recipe book, or instruction manual – their DNA. Our DNA is a mix of our biological parents DNA. Mixing of DNA occurs when an egg and a sperm, from our biological parents, fuse. Thanks to a cell’s DNA, it knows when to grow, and what to do next. In order to produce new cells and form all the parts of our body, our cells divide to produce two new cells (Figure 1). Before dividing, cells replicate their DNA and grow large. Cells can then become neurons and grow long protruding arms, or axons, to reach their target; become skin cells and have high levels of keratin; or, form the heart and beat in rhythm with surrounding cells. Some cells will migrate through our bodies to find their homes. Other cells may only be required for a short time. Cells may enter programmed cell death – a process termed ‘apoptosis’ – in order to make way for other cells. For example, apoptosis is crucial during embryonic development, as our fingers and toes begin to form while still connected via webbed skin1. Through apoptosis the connecting web of cells is eliminated, allowing individual digits to form. Adherence to these intricate and complex processes allows for our proper formation and good health, resulting in a human body of roughly thirty trillion cells2.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the cell cycle.

Misbehaving cells

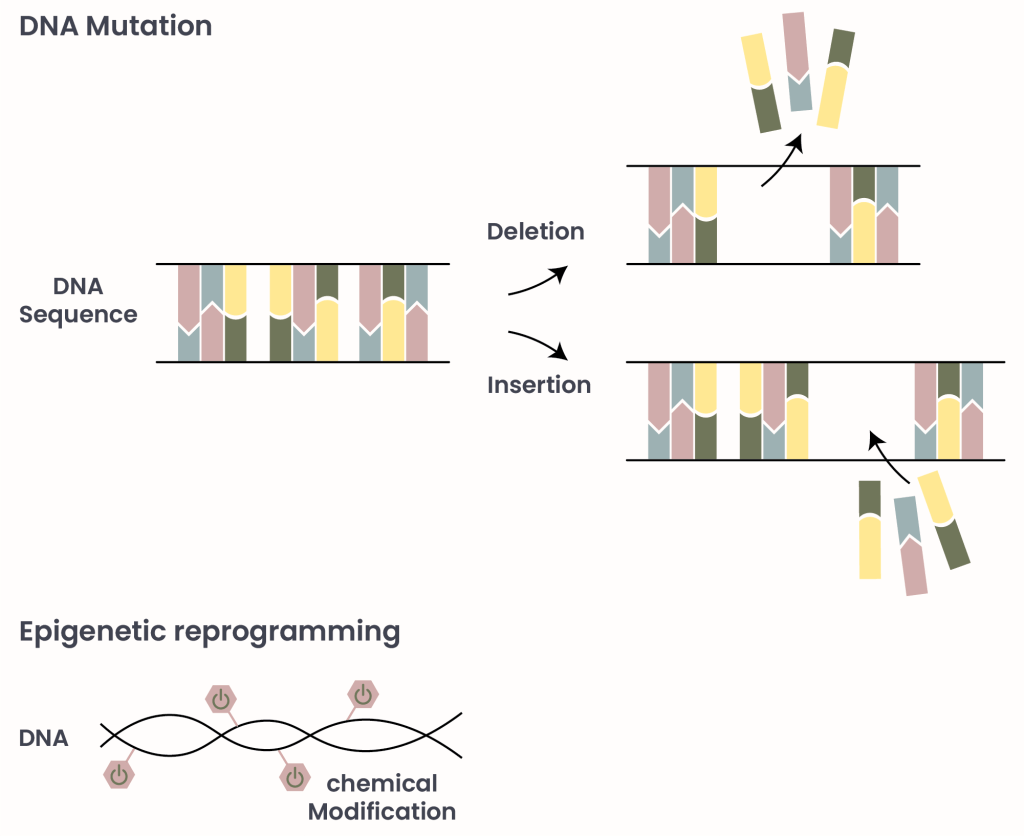

Recipes can get damaged over time as they are used more and more – smudges from fudge can smear words, and pages get torn, lost, or faded. Without clear recipes, chefs can make mistakes, similar to cells. Cancer cells are an extreme case of damaged instructions as they deviate from the highly coordinated series of processes that healthy cells follow. Cancer cell behavior deviation can occur because of DNA mutations, or because of other modifications involving epigenetics (Figure 2)3. A mutation involves DNA addition, removal, or relocation. If we consider our DNA to be instructions, then mutations are content errors resulting in steps being repeated, removed, or modified. Mutations can occur through various mechanisms, including during DNA replication or repair of DNA damage. DNA can be damaged by UV or toxins, such as those related to alcohol and tobacco consumption, partially explaining the link between consumption of these substances to cancer.

Figure 2. DNA modifications.

Even if a recipe is largely intact, a chef may try to perform steps in the right order out of memory. Performing each step at the right time is crucial. Cells use their epigenetics to know when and how much of each step to perform. If DNA is an instruction manual, then epigenetics are the footnotes that tell the reader where to go next, or to repeat a step. Epigenetics involves chemical modification of DNA, or proteins tightly linked to DNA, without introducing mutations. Epigenetic chemical modifications dictate when and how often nearby DNA instructions are read. Through controlled epigenetic reprogramming a stem cell can become a bone, heart, eye, or skin cell without modifying its DNA. Despite having the exact same DNA, epigenetics allows cells to display vastly different behaviors. However, if epigenetic reprogramming goes awry, cells may begin to follow DNA instructions too many times, too few times, or at the wrong time, resulting in incorrect cell functions. DNA mutations and epigenetic reprogramming constitute the modifications cells undergo to become cancerous.

The evolution of cancer cells

Just like recipes evolve over time as our taste, availability of ingredients, and tools available changes, cells can also change over time. Modifications largely occur randomly throughout our DNA. Modifications are not directed towards enabling cancer – but may do so if occurring, by chance, at the right position. A single modification often does not result in any change at all. Even if a cellular process is significantly affected, cells often recognize altered functions and trigger apoptosis. However, if a cell acquires a modification that allows it to ignore instructions for apoptosis, it could then survive, and continue to grow and divide. Cells inherit DNA instructions and epigenetic programming from parental cells, so daughter cells will also be able to escape apoptosis. Furthermore, cells receive signals from nearby cells that tell them when and when not to grow. Modifications could allow cells to continue to proliferate despite not receiving signals to do so. This can become a cyclical process: as cells divide more and live longer, they are more likely to acquire DNA mutations and undergo further epigenetic reprogramming. More mutations and epigenetic reprogramming can fuel further growth. Thought of differently, cells can evolve as they grow4.

Two shades of tumors

Not all tumors are created equal – similar to dough. Yeast allows dough to rise over time. Given too much yeast or time, the dough may rise too much. If allowed to rise even more, dough will spill out of its container. Similarly, cells growing too much can result in a tumor, and with the right modifications a tumor can spread to other parts of our body. Most tumors are benign, meaning they grow slower than cancers and do not metastasize, or move to other parts of the body. Benign tumors can still be harmful if they put pressure on a nearby structure and impair its function, and thus may be surgically removed. Certain types of benign tumors could adopt further modifications and become metastatic, and are thus closely monitored if observed5.

A tumor cell crosses from benign to cancer when it accumulates specific combinations of modifications. Unique properties of cancer have been dubbed the ‘hallmarks of cancer’ (to be discussed in a post in the near future)6. Cancer hallmarks allow cells to grow quickly, move through and persist in our bodies, and adapt to harsh microenvironments they may encounter. However, hallmarks could also be considered the Achillis’ heel of cancer: they distinguish cancer cells from most healthy cells, and therefore represent potential therapeutic targets while avoiding harm to most healthy cells.

Cancer is difficult to treat…

Improving a recipe can be challenging, as modifying any single step or ingredient will impact the entire dish. Similarly, while targeting cancer cells with medications, it is hard to avoid hurting healthy cells. Having identified so many hallmarks and other properties of cancer, one may think that we have studied cancer enough to allow for effective treatments. Unfortunately, almost all functions of cancer cells have been co-opted from healthy cells, and used in a manner not specified in their DNA or epigenetic code. Therefore, targeting a property of a cancer cell often also results in targeting healthy cells. Healthy cells suffering from cancer treatments lies at the heart of many side effects of medications.

Some modifications are common to many cancers, while others are rare but very important when present. Cancers differing one from another is a source of cancer heterogeneity, or dissimilarity between one cancer and the next. Heterogeneity can also exist between cancer cells within a tumor – adjacent cancer cells can be different, for example due to different mutations or epigenetic reprogramming. Heterogeneity of cancer, both between different patients, and within a patient between different cancer cells, results in the near impossibility of a one-size-fits-all treatment.

…but we are getting better at it!

The good news, however, is that through relentless cutting edge research we have identified and continue to uncover novel targets. Through identification of new targets we can develop more thorough treatments with less side effects. Engineering novel discoveries for use in medicine also continues to expand the medical toolbox for cancer treatment. While a miracle cure is unlikely, significantly improved treatments resulting in less pain, longer remissions, and longer survival are on the horizon.

- Gilbert SF. Developmental Biology. 6th edition. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; 2000. Cell Death and the Formation of Digits and Joints. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10048/. ↩︎

- Hatton IA, Galbraith ED, Merleau NSC, Miettinen TP, Smith BM, Shander JA. The human cell count and size distribution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023 Sep 26;120(39):e2303077120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2303077120. Epub 2023 Sep 18. PMID: 37722043; PMCID: PMC10523466. ↩︎

- National Cancer Institute. (8 Aug. 2024), The Genetics of Cancer. Cancer.gov. Retrieved February 9 2025 from http://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/genetics. ↩︎

- Ciriello G, Magnani L, Aitken SJ, Akkari L, Behjati S, Hanahan D, Landau DA, Lopez-Bigas N, Lupiáñez DG, Marine JC, Martin-Villalba A, Natoli G, Obenauf AC, Oricchio E, Scaffidi P, Sottoriva A, Swarbrick A, Tonon G, Vanharanta S, Zuber J. Cancer Evolution: A Multifaceted Affair. Cancer Discov. 2024 Jan 12;14(1):36-48. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-23-0530. PMID: 38047596; PMCID: PMC10784746. ↩︎

- Patel A. Benign vs Malignant Tumors. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(9):1488. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2592. ↩︎

- Douglas Hanahan; Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov 1 January 2022; 12 (1): 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1059. ↩︎

© 2025 WithinOncology. All rights reserved.

This article, including all text, tables, and figures, is the intellectual property of WithinOncology and its contributors. Unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or use of any content without explicit written permission is strictly prohibited. For inquiries, please contact us via the contact form.

Leave a comment